THE CITY IS HOME to a multitude of facts. And yet, how ordinary is the ordinary? In the public imagination, in India at least, Patna is an open city. It has surrendered to the might of scandalous stories. Kidnappings! Corruption! Crime! Here is a case that was a favorite of mine for several years. The journalist Arvind Das wrote in The Republic of Bihar about a conversation overheard in a train from Patna in 1991: A woman, distraught at her husband’s prolonged illness, was telling her son that she sometimes found herself wanting to commit suicide. The son responded that his father’s death would be more welcome. Das had written, “Why should you die, why not kill Babuji instead? If he goes away, we will get his gratuity and provident fund money and it is possible that I might even get a job on compassionate grounds. What use will your dying be?” Das noted in his book that the boy was only twelve years old.

THE CITY IS HOME to a multitude of facts. And yet, how ordinary is the ordinary? In the public imagination, in India at least, Patna is an open city. It has surrendered to the might of scandalous stories. Kidnappings! Corruption! Crime! Here is a case that was a favorite of mine for several years. The journalist Arvind Das wrote in The Republic of Bihar about a conversation overheard in a train from Patna in 1991: A woman, distraught at her husband’s prolonged illness, was telling her son that she sometimes found herself wanting to commit suicide. The son responded that his father’s death would be more welcome. Das had written, “Why should you die, why not kill Babuji instead? If he goes away, we will get his gratuity and provident fund money and it is possible that I might even get a job on compassionate grounds. What use will your dying be?” Das noted in his book that the boy was only twelve years old.

And yet, as often happens in Bihar, the state of which Patna is the capital, it is also possible to tell the opposite story. Das features in this one too. In Delhi, during a visit last summer, I went for a walk in the garden around Humayun’s tomb. My companion was the esteemed social thinker Ashis Nandy. We were talking about Bihar, and Nandy said that there were many news reports back in the 1990s about young Bihari men being forced to marry at gunpoint. In most cases, a youth traveling in a train would find himself looking up into the barrel of a gun. He would be asked to disembark and would be taken to a town or a village where he would be married to a girl whose family had guns but not the means to pay an expensive dowry. Nandy told me that he had asked Das, who was from a village only a couple of hours away from Patna, whether there wasn’t a lot of fear on the part of the bride’s family that their daughter would be abandoned or killed? Das had said to him: “But that too is Bihar! So far I have not heard about a single such case where the young woman has been harmed.”

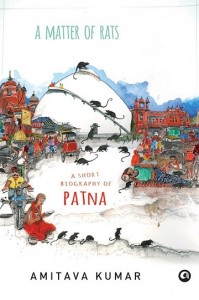

But that too is Bihar! When Nandy finished telling me his story, I thought of a line from John Berger’s Booker Prize–winning novel, G.: “Never again will a single story be told as though it were the only one.”It could be a credo for nonfiction writers. To show on the page that despite what you’re saying, there is another story waiting in the wings. The ordinary kept from being made extraordinary — the tame fascination with the exotic — because it is never removed from the context of surrounding facts. Rats are to be found in my parents’ home in Patna, yes, but they become real to me, as I sit listening to them at night, because of the research done on rats in New York City.

“It was years before I saw that the most important thing about travel, for the writer, was the people he found himself among.” This was V. S. Naipaul writing in Beyond Belief, an account of his travels in Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan, and Malaysia.What Naipaul was saying about travel to foreign countries is also true for the writer who is only returning home. [pullquote align=”right”]This long essay is about my hometown, Patna, but at its heart are stories about people.[/pullquote]This long essay is about my hometown, Patna, but at its heart are stories about people. People, not political programs. “Has Patna improved?” Questions of this nature are often directed at those who know Patna. I have little interest in answering such questions. The emphasis on the ordinary means that my attempt here has been to present stories of daily lives. My themes here are similar to what I would have explored if I were writing about people elsewhere: success, failure, love, death. I have written earlier that there are no people in postcolonial theory. Almost the same can be said about place. A term like “postcolonial” swallows up whole continents and nations. This book is about a particular place called Patna, and I cannot deny that my portrait is personal. In this, too, I’m reaching for the ordinary, paying attention to what remains obscure and whose value is overlooked. In the last paragraph of Here Is New York, E. B. White wrote about an old, battered willow tree in the city. He wanted the tree saved. White hadn’t ignored the vision of the tall towers and the terrible errands of the flying planes, but what mattered was the tree: “If it were to go, all would go.”In the pages of this book that I have written about Patna, I too have something that I want to save. I have in mind two residents of Patna who have spent a lifetime there. They have survived the city’s troubles and celebrated its achievements, and they will not be around forever. Patna is the place where I grew up, but those two are my real place of origin. And when they are gone, my link to Patna will be broken.

One final prefatory remark. The place of place is also in writing. In other words, a writer arrives at a sense of place not by mere accident of birth or habitation but by creating, again and again, a landscape of the imagination. I’m flooded with memories of my past grant applications: “Dear Sir/Madam, I am writing to apply for funds to travel to Patna to conduct research in areas of peasant unrest. My primary interest is in the cultural production of protest.” Articles, travel pieces, memoirs. A practice carried out over years of return, akin to a pattern of writing and revision. In a changing city, the urgent need to record my deepest associations. Even in fiction, the desire to put down precisely the arrival of the monsoon in Patna:

Rains lashed the house, driving water inside through the cracks in the windows, making the wooden window frames swollen and gray. The ceiling in the bathroom turned green and began to drip. If the front door was left open in the evening, frogs hopped in and took their place on the floor around the sofa, looking very much like well-fed but malcontent guests. The pages of the notebooks reserved for homework got stuck together and could only with some ingenuity be used to make paper boats. Binod and Rabinder would return from school with their hair damp and their clothes soiled with mud. Wet garments were spread to dry on every available piece of furniture and also under the sluggishly turning blades of the ceiling fans. There was a clothesline even in the kitchen. Most of the walls became furred with peeling paint and centipedes of different colors crawled on them and found their way onto beds and pillows. It suddenly seemed during those months that there was very little space in the house for its real inhabitants.

The mere act of typing these words, copying them from the page open in front of me, provides an entry into that place of writing. The location of culture is not so much a place but an active practice — the practice of writing.