The reality proved starkly different. The first leg of the trip was indeed by plane to Moscow, but once in Russia they were kept isolated in a windowless room for over a week with little food and no information. Eventually they were joined by small groups of illegals from Vietnam, China, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

The reality proved starkly different. The first leg of the trip was indeed by plane to Moscow, but once in Russia they were kept isolated in a windowless room for over a week with little food and no information. Eventually they were joined by small groups of illegals from Vietnam, China, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

They were then taken on foot through the Ukraine and Czech Republic. “Madam, it was winter and there was so much snow, sometimes till our knees,” Gurtej told me, his voice flat and eyes invisible behind his dark glasses. “There was a man in our group who got frostbite and he collapsed. He couldn’t walk anymore. The agent just left him there to die.”

Gurtej and several in his group were arrested near Prague after being abandoned to fend for themselves on a winter’s night in a “house” without a roof, somewhere deep in the countryside. “The agent just took off and said he’d come back for us the next day. But we realized if we stayed we’d die in the cold so we began to walk, even though it was dark and we didn’t know where we were going.”

A few hours later their group was arrested and held in a detention centre for around a month. They were eventually issued permits that allowed for short, unsupervised trips into town. On one of these outings their agent showed up again and spirited them away. Gurtej eventually reached Germany, his intended destination in Europe, two-and-a-half months after he’d left Punjab.

In Germany there were jobs available in the horticulture sector [pullquote align=”right”]In Germany prospective employers asked him to shave his beard and take off his turban.[/pullquote]but prospective employers asked him to shave his beard and take off his turban. “They thought I looked like a terrorist. But for me, my religion is everything,” said Gurtej, “and I refused.” “Then I heard in Italy they were less strict about these things, so I came here instead.”

We were standing outside a gurudwara or Sikh temple near the seaside town of Sabaudia. The building that housed the gurudwara had been a warehouse for stocking agricultural produce and despite the obvious care that had gone into maintaining it, retained a makeshift air. Outside, the yard was little more than an unpaved dirt track.

Motorbikes, bicycles, and a few cars crowded the yard. I reckoned 400-odd devotees had come in that morning from the surrounding farms for the Sunday prayers. Gurtej said the numbers could swell to 800. In all there were 35 gurudwaras in Italy, including some of the largest outside of India. But the one in Sabaudia was unimposing.

It had been inaugurated only a few days after the attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York on September 11, 2001. When neighbours heard the gathered Sikhs shouting out “Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal,” the traditional jaikara or “shout of exaltation” Sikhs use to express religious joy, they called the police, convinced that they were ‘terrorists’ celebrating the attacks.

“We’ve had a tough time since then, trying to explain to people we are not terrorists,” said Gurtej, “and they mostly get it now.” But it wasn’t uncommon for workers returning home on bikes after a ten-hour shift in the fields to be pelted with lemons and stones by Italian kids.

Why, I asked? “Because we look different,” replied [pullquote]”It’s not like life is without humiliations back in India.”[/pullquote]Gurtej remarkably serenely. “They don’t really understand what they are doing.” How do you put up with that kind of humiliation, I persisted? Harbhajan joined in. “The money is better and it’s not like life is without humiliations back in India. At least here we don’t have to deal with the kind of corruption we face back home.”

When I told friends in Brussels this story they laughed out aloud. They’d never imagined anyone would look at Italy as a paragon of upright living.

At the gurudwara that morning the granthi was reciting prayers. “Pain is the remedy,” he crooned. “The joy of mammon is the disease.” The irony of the sentiment was lost on the gathered congregation. They sat, men on one side, women on the other, heads covered, eyes closed in remembrance, or perhaps simply exhaustion, and rocked gently back and forth.

Outside the gurudwara, we were joined by Marco, the Italian sociologist. Gurtej and Harbhajan chatted with him easily, in heavily Punjabi-accented Italian. I asked them how they had learnt the language. Had they taken classes? Harbhajan burst out laughing. After a whole day in the field or felling trees, who had the energy to attend classes? They’d learnt on the job.

“If we didn’t know the language who would hire us? We wouldn’t be able to understand instructions,” said Gurtej. Harbhajan added, “We’ve lived here ten years, madam. Even an animal would have learnt Italian in ten years.”

I thought of all the unemployed Walloons in southern Belgium who hadn’t learnt Dutch in a lifetime, despite the availability of jobs in Flanders that the language would have been the key to securing. And this was far from a uniquely Belgian problem. While in Italy I came across an article in the New York Times about a French town, Sélestat, on the Franco-German border. Sélestat suffered from high unemployment although plenty of work was going in the next-door German town of Emmendingen. But Selestat’s unemployed remained either unwilling or unable to learn German. The mayor of Emmendingen was quoted as saying, “There is a job here for anyone who can count to ten, but one needs to count in German.” The French couldn’t.

Harbhajan was wrong. The reason the Indian immigrants had learnt Italian was not because they had lived in Italy for ten years but because no one would pay them an unemployment benefit if they didn’t work, and they needed to speak at least basic Italian to get a job. They had no choice. An accident of birth had meant they were shut out from the privileged world of the European workforce.

But what of their children? That afternoon Marco took me for a walk along Sabaudia’s lake. Flanked by low-lying hills, the lake and the sea beyond it glowed palely in the weakening sun. I spotted three local teenagers sitting on an embankment, smoking cigarettes and guffawing at shared jokes. One of them was obviously of Indian parentage. What was his future going to be like?

Like other second-generation Indian immigrants [pullquote] He looked like a Punjabi on the outside, but dressed and spoke like an Italian. [/pullquote]who’d been born in places like Latina and gone to school with Italians, he looked like a Punjabi on the outside, but dressed and spoke like an Italian. Since Indian immigration in the region was a relatively new phenomenon, the second generation was still mostly of school-going age. The few who were older had already begun to move up the economic value chain. In Rome I noticed young Indian bus conductors and waiters in restaurants. Like their Italian contemporaries, they showed little appetite for the gruelling farm work that had brought their parents to the country.

But given the economic stresses Europe, and Italy in particular, are facing, jobs as a whole are scarce. “Docile” Indians toiling deep in the countryside might have easily fitted into Italian society by virtue of being content with remaining hidden away from that society. Educated Italian-Indians competing for the limited number of jobs in the service sector however, might not be accepted as easily.

These second generation Indians are denied Italian citizenship and granted residence permits only if they can prove employment. The potential for friction is obvious, as expectations rub up against reality and pliant, “humble” first-wave immigrants give way to a disillusioned, “demanding” new generation of Italian-Indian residents.

* * *

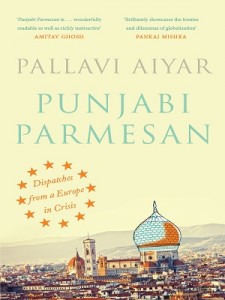

Pallavi Aiyar is currently based in Jakarta, from where she writes about Indonesia for Indian and international publications. An award winning journalist, Pallavi Aiyar has worked as a foreign correspondent for over a decade, reporting from China, Europe and South East Asia. She is the author of the 2008 China-memoir, Smoke and Mirrors, which won the Vodafone-Crossword Popular award. Her 2011 novel, Chinese Whiskers, a modern fable set in Beijing, was published in the United States, Italy, Belgium and India. She is also lead author of a new Lonely Planet guide to China for the Indian market. Her latest book is Punjabi Parmesan, Dispatches from a Europe in Crisis.