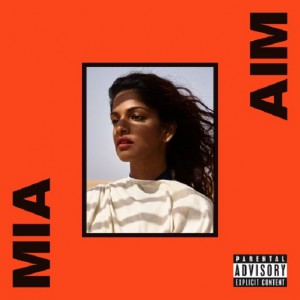

Ready. Aim. Fire. I wonder if this sequence of words sums up the context from which M.I.A., rapper, singer-songwriter, visual artist, activist et al., Mathangi ‘Maya’ Arulpragasam derives the title for her latest album, AIM. Of course, there are other literary considerations to be taken into account, like the fact that the album name is eponymous, even if a palindrome. “Aim” resounds in various frequencies: aim, as in to target; aim, as in to aspire to; aim, as in to intend. (Read: the opposite of missing in action.)

M.I.A. has long been preoccupied with social justice, it being the dominant theme in both her early and latest work. Popularized by the appearance of her song “Paper Planes” in the 2009 Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire, she vocalizes themes concerned with equality, geography, warfare, displacement, collective memory, religion, and essentially any social, economic and political factors that synergize, or antagonize, the simultaneously singular and plural identity of the modern individual — all with a sense of urgency, dissonance, debate and most importantly, from some accountable, inside place within the global chaos.

“The songs on this album harness identity as both a means and end of discussion.”

In AIM, M.I.A.’s predominant speaking voice both resolves and enforces some distance between her, the listener and the subject matter, evident in the frequency with which she drops word bombs using “I”, “you” and “they”. It’s as if, like atoms, each individual’s contribution to evolution is so germane to the historical narrative, if one pivot were missing, the entire system, and in this case the entire song, would crash.

The songs on this album harness identity as both a means and end of discussion. In their very transformative and transmutive abilities they reveal how identity is not static, nor perfectly divisible. There is no “I” without “you”, there is no “we” without “you” or “me”. “Freedom, I’dom, Me’dom, Where’s your We’dom?” M.I.A. sings in perhaps the most popular track on the album, “Borders“.

Like one would in a post-modern grocery store that sells human characteristics, she picks ingredients per her taste buds from an interconnected smorgasboard, to make sense of an internal pattern or make-up. “I don’t lose focus like a German called Sven/My third eye’s open and my focus ain’t joking,” she sings in “Go Off“. The point, I think? Again, if variations exist within the same persons, there can be no consolidated identity. In a culturally sensitive environment that’s generally hyper-aware, identity is composite — pieced together by influence.

Where we were once only outspoken or only benign, today we are both. We are also spiritual and terrorizing, we are devastating and devastated, we are good and bad. M.I.A. also reveals elements of nostalgia and hopefulness for peaceful coexistence in her carefully mutated and meandering vocals. She’s almost idealistic about the past, while demanding that said ideals come true in the future.

She also sculpts a deliberate distance between highbrow theories and daily life lived on the ground. It’s in the conversational vernacular she adopts where the effect of her demagoguery takes the most persuasive shape. Whether it’s name-dropping high street items and pop culture references in “A.M.P. (All My People)” or describing a frame of mind through a fire mood emoji in “Survivor” to representing the “thinking generation” in a likely description of the ten things a millennial might consider on their way to work in “Ali R U OK?”, M.I.A. is the voice of the times.

The estrangement, the bewilderment, the exasperation her enunciations reveal are all a consequence of being alive in an era of the individual, where pressures run high and boundaries run low. I am tempted to make the connection to Dadaist poetry of the 18th century, an ideological revolution against the very concept of art by propogating nonsense, similar to the incoherent “dada” sounds babies tend to make. But a work of art, whether nonsense or not, by its very nature is political, because it can’t help but express some claim on reality. In mocking today’s reality, M.I.A. takes her stand: “What’s up with that?”

“In mocking today’s reality, M.I.A. takes her stand: ‘What’s up with that?’”

Interestingly, in an interview with the Guardian M.I.A. reveals, “In my head this is like the love album,” she says. “It’s a cute album, My Little Pony, compared to what I usually make.” In many ways M.I.A.’s chuckle is telling. In “Freedun”, there are marked shifts in voice, temporality and scope. From her verse:

I don’t need any audition

I just got my own little mission

It grew bigger than a politician

Yeah, history is a competition

Do you wanna sign my petition?

to celeb-sweetheart Zayn Malik’s chorus:

All the stars are still shining

But you’re the only one I see

I can feel when your heart beats, yeah

Babe, you can’t keep your eyes off me,

there is an undeniable shift in focus and concern — in some instances heroic, impacting and memorable; in others, a highly politicized ego seeking validation and support to assume the lead in the rat race. Could it be that M.I.A. recognizes the infallibility of the human spirit here, that is predicated on dichotomy?

M.I.A.’s concerns are both grand (the refugee crisis) and mundane (the personal life issues people tell you not to focus on when there is so much else wrong with the world). The coincidence of the two sharing lines in the song only suggests that AIM is a manifestation of an individual who concentrates on and cares about the world . . . and themselves. Most post-modern philosophers would have echoed this sentiment. Particularly Heidegger comes to mind, and he suggests that life is always lived in some mood that cuts through an objective reality through a subjective perspective, so much so there can be no world outside the way one sees it.

The relationship between the global and hyper-local ensues through most of the album. NPR shares M.I.A.’s own assertion that her “take on racial strife is more global than before — perhaps even a throwback to the ‘peace and unity’ vibe of the 1990s.” The cross-over exists not only in the lyrics but also in the haunting way musical rhythms from across the world blend, break and blur into each other in AIM.

“…musical rhythms from across the world blend, break and blur into each other in AIM.”

The score feels ambiguous, alien, belonging to a different wavelength. Percussionist and punchy, the sounds vibrate in the ears long after Spotify has gone to sleep. With Trap influences, each high is as high as it’s next low — the circle of life, maybe? High energy dance vibes, it’s the kind of music that gets stuck in your head, even if it’s against your will.

M.I.A.’s minimalist excursions in AIM seem more in tune with provocative literature, full of plot and tropes and context, but flowed through the audio-visual format. Experiments with form, function and feeling carry this album into new territory for M.I.A. Many critics are calling AIM’s contemplative nature callous and lacking creativity. But, theoretically speaking, form is a calculated extension of the message of an art work in that, as a vehicle for the message, it influences the message that is ultimately received, and more importantly, the way the message is received.

Given the aloofness and winding repose of her reflections, does it almost feel as if she could have texted us some parts of these songs? What would that say about how the mass populous communicates today? What are we sending and receiving, and, how are we sending and receiving that which is being sent and received? She says, “We’dom smart phones/Don’t be dumb!”

* * *

Dipti Anand is a poet, writer, editor and academic, living and working in New Delhi, India. To connect with and read more of Dipti’s reverie and creative work, visit www.diptianand.com.