THE WORLD AS IS

The basic requirement for the understanding of the politics of change is to recognize the world as it is.

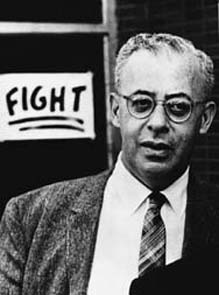

Those words, uttered by the famed organizer Saul Alinsky, echo in my head, often when I’m helping to organize political events with friends, or listening to their discussions on how best to harness rage and frustration into something positive. Over the past few weeks, those words have grown louder, especially as Senator Kamala Harris ascends onto the national stage as an early Democratic Party presidential hopeful, and as members of the Democratic Socialists of America convened for one of their largest conferences ever.

It is clear now that there is great potential for fighting back against Trump and the right-wing. However, there is also the growing possibility of divisions forming among those invested in social justice, which could stop us from improving the lives of the poor, and people of color.

Understandably, some want drastic change, to dismantle all institutions of unjust power. And others desire winning elections, even if that means believing in candidates who aren’t 100 percent progressive. As someone learning from activists who sacrifice their body and soul for the greater good, I too have wracked my mind over how to approach revolutionary change.

Alinksy, whose parents were poor Russian Jewish immigrants, grew up in Chicago during the Depression. After graduating college, he became a labor organizer, and trained organizers around the country, sharing methods on how to chip away concessions from the rich and the powerful. Although there are legitimate criticisms to be made of Alinsky, his vision of politics still resonates.

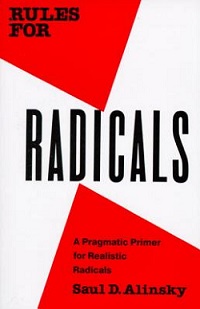

In Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals (1971), Alinsky lays out the need for young revolutionaries to bring more people into the fold. Alinksy believed that for the kind of massive change that many young people wanted, they needed to connect more with others and make them also see the value in raising their voices against the powerful.

Even groups such as the Black Panther Party seemed to express this balance between what others might see as “reformist” politics (i.e. reaching out to the community, deepening relationships with white Leftists) and a revolutionary ethos. What the BPP, Alinksy, and others understood was that choosing between reform and revolution was a false choice, one that can distract from the mission of winning back power and improving peoples’ lives.

THE BPP AND THIRD WORLD LEFT

The Black Panther Party (BPP) began in Oakland in the late 1960s. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were two of its main co-founders. BPP was started when the civil rights movement, led by Dr. King and others like him, began to spread into the North. However, unlike the South, there were no racist southern sheriffs for the entire country to root against. Instead, there were housing covenants by white residents, and countless African Americans policed and pushed to the edge, without access to decent housing or jobs. After King’s assassination, many young black men and women decided enough was enough.

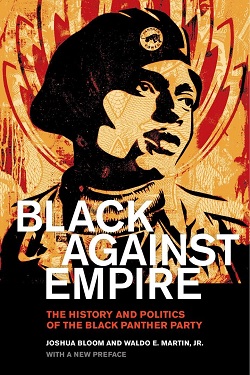

When riots happened, especially the ones in places like Watts, Huey Newton, who had an insatiable appetite for political theory, viewed them as uprisings. According to sociologist Joshua Bloom and historian Waldo E. Martin, Jr., who researched the Black Panthers, publishing their analysis in Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (2012), the BPP, under Newton, knew that the only way to have a revolution was to build up a base among those disaffected in places like Watts and Detroit.

Soon, the BPP formed branches across the country. Even when Newton and countless other leaders of the party were jailed, the party expanded. It did this by acknowledging that people in the community needed to be engaged with. Similar to Alinsky, the BPP knew that although many people suffered, not everyone was comfortable in taking to the streets. They had to meet the people where they were politically and intellectually, and try and raise their consciousness to make them recognize their own potential in creating positive change.

Therefore, the BPP created an impressive array of community programs that worked to meet the food, health, housing and other needs of those they wanted to convince. Further, the BPP’s politics wasn’t based on abstract ideas of justice, but rather, fueled by a revolutionary nationalism that was socialist in nature. Their ideology of taking apart capitalism, along with white racism, and other forms of injustice, meant that they could also, make contact with non-black allies without losing their revolutionary edge.

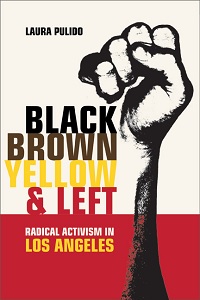

The Third World Left, written about and discussed by professor Laura Pulido, mapped their own politics on what they saw accomplished by the BPP. In Black, Brown, Yellow & Left: Radical Activism in Los Angeles (2006), Pulido focuses on groups like CASA (El Centro de Accion Social y Autonomo) and East Wind, which hoped to be the voices for their own communities in a similar way.

CASA, which represented Mexican Americans, shared the belief that their fight was racial and economic. Their demands were also a mix of revolutionary and reformist, including unconditional amnesty for all undocumented, while also, supporting the right for workers to unionize. As East Wind was formed by Japanese Americans and other groups active in the Asian national movement, members sought to raise awareness around drug addiction, which was a major concern in the community. Like BPP, East Wind also built relationships with other groups of color and white progressives.

Unfortunately, groups like the BPP, CASA, and East Wind collapsed, due to internal divisions, and to the rising tide of police surveillance and FBI intervention. Ultimately, the balance of reformist and revolutionary politics went missing.

A NEW REVOLUTION

Finally, as South Asian Americans, Asian Americans, and people of color who want the country to become democratic, it is our responsibility to maintain that balance of reform and revolution, and to continue meeting the people where they are. Most importantly, it is up to us to support and follow the example of organizations that are already doing the hard work of pushing for systemic change.

Desis Rising Up and Moving, Adhikaar, CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities, and East Coast Solidarity Summer are some of the most prominent and well organized of these types of organizations.

Founded by working class Asian American women in 1986, CAAAV has worked with low income and marginalized communities across New York City. According to Cathy Dang, Executive Director, their work on programs, such as the Chinatown Tenants Union and NYCHA Organizing Project “organizes and develops the leadership of tenants to fight for improved living conditions, landlord and NYCHA accountability, language access, and long-term preservation through rezoning and anti-displacement policies,” and “Asian Youth in Action is a youth program with young people from all over NYC who come together to develop their skills as organizers, supports the housing organizing of the tenants, and a space where they develop their political analysis.”

“It is up to us to support and follow the example of organizations that are already doing the hard work of pushing for systemic change.”

Similarly, ECSS provides an “educational and community building space for young South Asians ages 15-23 (ish),” Eshani Dixit, a core organizer explained, adding, “Our main focus is putting on an annual summer retreat that is roughly five days in length, where we do a variety of workshops and community building exercises. The specific focuses change from year-to-year but our major themes are generally social justice oriented and center around the concepts of anti-racism, anti-sexism, queer and trans liberation, anti-imperialism etc.”

Both CAAAV and ECSS encourage people to think critically about the system without losing sight of important legislation.

When I asked about what ordinary people could do to defend themselves against Trump’s policies, Dixit responded, “There are so many things you can do! The simplest thing would be to email or call your legislators when a bill is on the table that you vehemently oppose. Other more intense things include going to rallies or marches, organizing or attending community meetings, or directly lobbying your elected officials. I think another thing that’s really important too (especially for white people and basically anyone who has a family member or friend who voted for 45) is to have critical conversations about this administration and begin the work of directly confronting the racism and hatred that got him elected.”

CAAAV has always been invested in empowering others to think for themselves, and to not stray away from mainstream politics.

“Educate themselves on their rights from the police, FBI, CIA, and ICE so they can defend themselves and support others when their rights are being violated (immigration, police harassment, political repression, religious or political surveillance, etc.),” Dang explained on what people can do to resist Trump, “Get connected with organizations in their neighborhood or City to fight for local protections and continue the work they have been doing around policy change. If able, attend actions responding to federal policies that are repressive on the people and continue to fight for a world that we still believe is possible. Where possible, push for local (city and state) control and protection until we can secure federal protections again. Get involved with the 2018 elections in Congressional races.”

“People have to be heard, persuaded and understood.”

Although CAAAV, ECSS, and others differ in many ways (CAAAV and ECSS are explicitly non-violent/peaceful), they all confront the reality that many people are too disheartened, or too busy (working multiple jobs to stay afloat financially) to immediately care about the bigger picture. People have to be heard, persuaded and understood.

Ultimately, the desire to push away Reagan/Clinton-era politics, and the anxiety of becoming part of the system if staying too long to change it, should remain guiding principles. But, taking power away from the white supremacists and capitalists will be a slow and dirty process. Those of us who are economically and educationally privileged cannot and should not step aside from participating in the system, or worse, ignore bills and reforms that can help improve peoples’ lives presently, because of our hope for a revolution that can take decades to arrive. Regardless of personal choice, countless Americans need access to healthcare, food, running water, shelter, right now.

Famed political theorist, Michael Walzer, shared the advice of a close friend on how to think about politics during a Trump administration. “Don’t think, he said, of your own scruples; think of the welfare of the most vulnerable people in the country. And then vote, gladly, for the candidate who minimizes their vulnerability,” Walzer shared.

Either, we collapse under our egos, or we commit ourselves to this struggle with sound body and mind, unsure of what might happen next, but confident we have to keep taking steps that move us all forward.

* * *

Sudip Bhattacharya is currently a Ph.D. student in political science at Rutgers University, where he focuses on race and social justice. He has a Master’s in journalism from Georgetown University, and has had his work published at CNN, The Washington City Paper, The Lancaster Newspapers, The Daily Gazette (Schenectady), The Jersey Journal, Media Diversified (Writers of Colour), Reappropriate, AsAm News, The New Engagement, and Gaali Gang.