The Reality: “These types of stories need to be heard”

Before moving away to Philadelphia, Sarah Madha shared a one-bedroom space with her mom and four siblings. Although it can be stressful, and for an outsider, seem unimaginable, Madha explains, “We always grew up sharing space, so we managed to make it work.”

Madha, who worked four jobs while in college, accepted that for her to keep moving forward she couldn’t dwell on her situation. Instead, her family had to constantly find ways to make ends meet.

“There isn’t time to have a special crisis about it,” she said, “If you don’t figure it out, you will end up homeless. If you don’t do it, you won’t have food or shelter.”

The reality of Madha’s life and the lives of countless working class, poor, and low-income South Asian Americans has often been missing from discussions on social justice and political representation.

Usually, class and income inequality are made irrelevant, with research and media reports pushing forth a narrative of Asian Americans succeeding economically and achieving the so-called American Dream. According to Pew Research Center, Asian Americans are the “highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group in the U.S.”

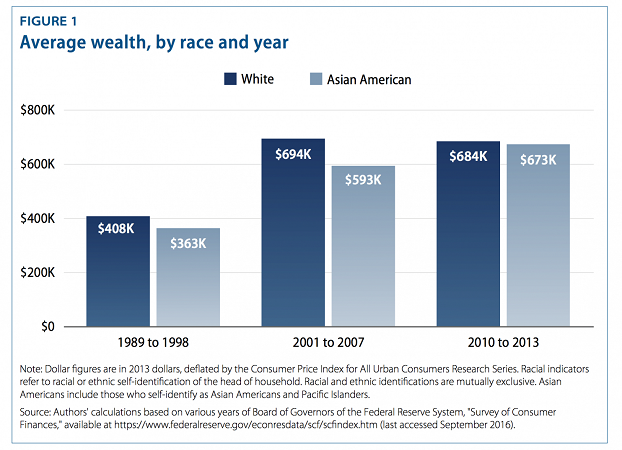

However, as social scientists and activists have focused their attention to the intricacies of Asian America, it is becoming more obvious how superficial this monolithic image can be. As The Washington Post reported, although the richest Asian Americans earn the most, the poorest Asians are still below the poorest whites and most importantly, the income gap among Asian Americans is the largest, when compared to all other racial groups.

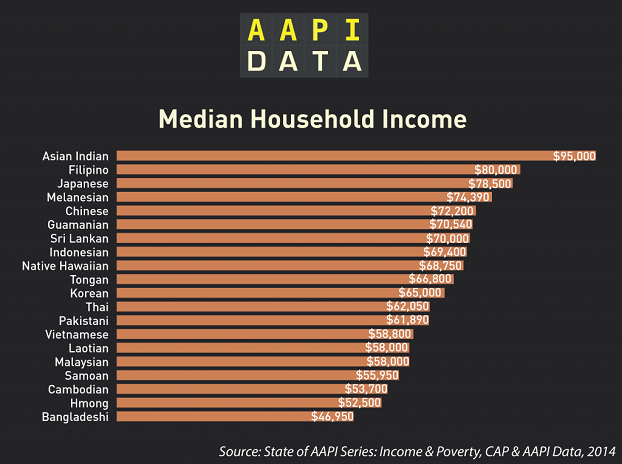

Furthermore, when the category of South Asian is disaggregated, one realizes the relevance of class and income. For example, Pakistani Americans, as reported by AAPI Data, have 16 percent living in poverty, which is higher than the 12 percent for all Asian Americans. The median household income for Bangladeshi Americans is reported to be the lowest among all Asian American subgroups studied by AAPI, at around $46,950, way below the median for Indian households, which was $95,000.

Jagpreet Singh, a community organizer in Queens, also grew up in a working-class household, and now, serves the needs of low income residents in the borough, many of whom are South Asians.

“A lot of them work within what we call the informal economy, like day laborer type jobs, working at restaurants, working within peoples’ homes, nail salons and parlors,” he explains, “The other half would be some taxi drivers, truck drivers, lower class, paycheck to paycheck type of folks.”

Singh’s main mission is to organize residents around the issue of affordable housing. Although New York City has set aside rent-controlled property, big developers/corporations have found ways to continue gentrifying neighborhoods, including areas populated by poor and working-class South Asian Americans. Developers confuse and misinform residents who are not English proficient. This causes many to leave, which allows the developer to raise the rent as high as 20 percent prior to someone else moving in. According to Singh, big-time developers, who don’t need all their units to be immediately filled, also hold onto vacant apartments, as property values skyrocket.

This lack of affordable housing leaves many families vulnerable and unable to access social mobility.

A report published by SAYA (South Asian Youth Action) states that “over one-quarter of South Asian youth in New York City live in poor households, as defined by the federal poverty level (FPL),” and in Queens, “South Asian youth are more likely to be poor than the average youth in the borough.”

Singh believes that the stories of those struggling have yet to be acknowledged by the larger South Asian American community and general American public.

He explains, “The stories of folks around struggles in immigration and working in the informal economy and being harassed by bullies, such as street vendors harassed by small business owners, these types of stories need to be heard from too.”

The View From Above: “To be poor is looked down upon”

Incorporating an understanding of how class politics and income relate to South Asian Americans will force us to recognize the systematic and structural forces damaging peoples’ lives, including capitalism.

Figures such as Karl Marx recognized the inherent dangers of capitalism and how it serves to benefit the rich and the middle class while leaching from the blood, sweat and tears of those below. Although the theories of Marx and Engels must be updated to match our modern era, much of what they said still rings true. In “Wage Labour and Capital,” Marx explains how workers produce goods and services that only make their bosses happier. The workers themselves use their wages to purchase items they need, such as food and shelter. Therefore, while the managers accumulate wealth, the worker is simply trying to survive, which echoes much of what Sarah had said earlier.

“We could never go to J.C. Penny or Target. That’s a splurge,” she said. “We usually find things in a thrift store. We usually work with each other’s wardrobes, with each other’s hand me downs.”

For Prabhjot Kaur Khangura, whose father had been a truck driver and whose mother saved every penny, paying for rent was a constant worry. Khangura was unable to attend school trips, since the $25 fee was sometimes too much for her parents to afford.

Among South Asian Americans, this embrace of capitalism, of so-called meritocracy and the American Dream, has also made it more difficult for those struggling economically to ask for help. In many South Asian American cultural spaces, to be poor is looked down upon.

“You have people in poverty who can’t afford things but too ashamed to reach out to get things that matter, like healthcare, or rent,” Khangura said.

“At the end of day, there are systems of oppression that we’re entangled in that we don’t critically think about. We are part of a system that can come at us at any moment,” said Sara Haq, referring to how many South Asian Americans, even those who are economically less well off than their peers, start to believe that their sacrifices will all be worth it someday.

Haq’s own family immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1990s. Her father, however, was accused of a misdemeanor crime he didn’t commit, but following the advice of his lawyer, he took a plea bargain, so he could move on with his life. He worked as a cab driver, and with a family support system, they were eventually able to own a home in the suburbs of Virginia.

However, in 2013, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents detained Haq’s father, because the misdemeanor was still on his record, and he was a green card holder. Suddenly, whatever minimal gains they had made were wiped away. After being locked up in a facility for nearly four months, Haq’s father was forced to return to Pakistan, and soon after, Haq’s mother joined him.

Haq, who is now a Ph.D. student in Women’s Studies at the University of Maryland, urges all South Asians, especially those with economic privileges, to begin the process of stepping back and analyzing the bigger picture, of how capitalism, merging with racism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, has produced a society primed to dehumanize and marginalize entire groups of people. That capitalism, intersecting with race, gender, and sexuality, inevitably creates unjust hierarchies of power.

The Way Forward: “Building class consciousness”

Madha, Khangura, Haq, and others echoed the repressive environment certain South Asian Americans have created, which makes it difficult for issues of poverty and class to be discussed, even among South Asian spaces that skew liberal.

For Khangura, fighting against white supremacy remains a key concern, especially given the current climate of fear and hatred. Yet, this focus on only combating whiteness can deflect attention from those in the Desi community, who are privileged by class and benefit from their economic status.

“When you want to critique capitalism, it’s difficult,” she explained, “It’s not an easy target because it requires more internal introspection and everything you know and the values of your community and your own. You have to be willing to unpackage that you’re participating in capitalism. Taking the spotlight and shining it upon yourself which makes it different.”

Haq, like Khangura and Madha, urges South Asian Americans to continue raising the political consciousness of their communities, to build bridges with other groups of color, especially African Americans, and to not buy into the myth of meritocracy.

“The point is to step back and question class politics and question racism,” she said, “What does it mean to be more mindful of where we stand as a classed person? It’s not good enough to donate to your local mandir or mosque. It’s not good enough to send money back to India or Pakistan.”

Building class consciousness, and breaking down anti-black bigotry and sexism will take effort and those interviewed were aware that it would be a slow and gradual process. But all also agreed it needed to happen sooner than later.

However, the most basic and necessary step toward creating this coalition and solving class inequality depends on the simplest of acts, one often overlooked by Desis who are economically privileged and hoping to engage with those from more marginalized communities.

“Just ask folks,” Madha said, “You can just ask folks what they need and they’ll tell you what they need.”

* * *

Sudip Bhattacharya is currently a Ph.D. student in political science at Rutgers University, where he focuses on race and social justice. He has a Master’s in journalism from Georgetown University, and has had his work published at CNN, The Washington City Paper, The Lancaster Newspapers, The Daily Gazette (Schenectady), The Jersey Journal, Media Diversified (Writers of Colour), Reappropriate, AsAm News, The New Engagement, and Gaali Gang.