I grew up learning to understand Bangla (how Bengalis refer to the Bengali language) and English at the same time — English from watching television and Bangla from my parents. Going to school helped me learn how to read and write in English. Learning to read and write in Bangla was of no interest to me.

I’ll never use it or need it, I thought as my mom tried to teach me the Bengali alphabet in failed attempt. The script was too hard to remember when I was a child.

My mom had a hard time trying to explain to me why I should learn how to read and write in Bengali. Because you should, she would say. I’m not going to just because you tell me to, I thought. Now as an adult, I realize what she was trying to say.

* * *

I did not live in a Bengali community so everything I picked up regarding the language was from my mother, who I spent most of my time around, and her regional dialect. She never spoke to me in English even though she understood and knew how to speak it.

Learning English was compulsory in every school even in villages she used to say. But she never spoke it unless she was in a circumstance that required it. Everything — from being scolded, to learning how to chop onions, how to make scathing insults, and hearing obnoxious jokes — I learned in Bengali from her.

“Everything…I learned in Bengali from her.”

A memory she frequently shares with me that I can’t recall was a compliment I got when I was a child.

“You know when you used to speak Bangla you used to get so many compliments. People would say, ‘wow how smart she speaks sadhu bhasha so well and clearly like a mini adult.’ You take after your dad’s mom. Both of you have this blade-like memory and penchant for details about the strangest things.”

Sadhu bhasha (literary language or formal language). Academics and linguists define it as used in literature, but I use my mother’s understanding of sadhu bhasha as formal language. It uses a lot of Sanskrit-derived vocabulary, especially where my parents are from. But it is not fixed. It has also gone through changes now with some Farsi, English, Pali words intermingling here and there.

My mother’s regional language and dialect is closest to the standard taught Bengali language (Cholito bhasha) because the standard taught Bengali is based off the dialect of Nadia district, a central region of Bengal now divided between West Bengal and Bangladesh. So, I developed good literary comprehension of it by the standard rubric, but illiterate people from the region can understand, comprehend, and speak it too because of the strong presence of oral inheritance.

“This is just my experience of how I connect to my mother’s language.”

But this is not to take away from a lot of beautiful and diverse dialects, literature, and oral traditions which get overshadowed by standard Bengali from other regions such as Sylhet, Chittagong, Dhaka, Noakhali, and many others. This is just my experience of how I connect to my mother’s language.

* * *

My maternal grandmother, who did not finish school past the third grade, had a very interesting way of relating to language. She fascinated me. To me, she was the perfect living metaphor of how the complexity of language and its history plays out in everyday life.

She would always go back and forth between Sanskrit derived Bengali words and Farsi derived words. Sometimes she would use them both at the same time. For example, when she would talk about the sky and the earth she would say akash patal, aasman zameen:

Look at that temper she’ll break the akash patal, aasman zameen with it.

Some people say that you can tell which side of Bengal a Bengali is from by what they say. For example, the word salt. It is more common for West Bengalis to use the word noon and for East Bengalis/Bangladeshis to use the word lobon. My grandmother would use both. She blurred those distinctions and ultimately resisted the divide of culture caused by partition. She grew up in a central region of Bengal, with the vocabularies of East and West Bengal mixed in her language.

Aro noon-lobon de/ Give me more noon-lobon, she would say.

The same for the word bath. Snan (sanskrit) and goshul (arabic).

Ami snan korbo/ I’m going to go for a snan or Goshul kore ashlam/ I just took a goshul.

And many other words and phrases.

* * *

Parts of the Bengali language are derived from Sanskrit, Farsi, Pali, and other sources such as Portuguese and Chinese. Many of what are labeled or codified as Hindu or Buddhist words, terms, or concepts are used by many Bengali Muslims as well. For example, the word attah in Bengali, derived from Pali, is a word that means “self” in the Buddhist context but as Bengali Muslims we also use that term but understand it to mean “soul”.

Why?

Because Buddhism was widespread across Bengal especially under the Pala Dynsaty, and when Islam came the concepts began to merge. Words began to be inherited by the new cultural contacts or old words began taking new meaning.

“To me, it was something I didn’t think about. It just made sense.”

Take the word shanthi — peace, calm, tranquility — a word derived from Sanskrit used in day to day language. My mother would say in distressful situations “Khoda’ tala, iktu shanthi dao” — “God, give me a little peace.” Khoda is a word derived from Farsi which has Zoroastrian connections. It was completely normal for me to hear such phrases with mixed terminology. To me, it was something I didn’t think about. It just made sense.

* * *

I consider English to be my fluent and dominant language because I can express myself best in it. It wasn’t until grad school that I began to realize that the two languages were intertwined and co-dependent for me. Now I realize the struggles I have with being tongue tied and not being able to express myself verbally very well in English sometimes even though I am fluent in it.

I thought it was from jumpy nerves and being shy. The language component never crossed my mind. It was during grad school that I finally learned the grammar, history, and to read and write in Bengali.

I finally gained back my equilibrium in verbal and written expression and memory retention after struggling to figure out why I was having those problems. It made such a big difference to tap into and give attention to that part of my mind I ignored, thinking it was useless.

My comprehension is excellent though I still can’t string together sentences in Bengali to express myself in conversation. The act of translating songs, poems, stories, and inserting words and concepts from Bengali into my own poetry helps with the practice of maintaining both languages.

Now I know why my mother tried to get me to learn Bengali.

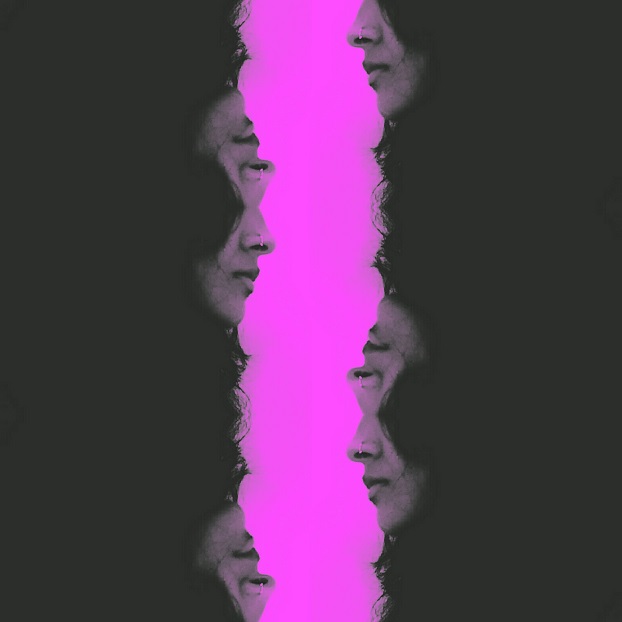

Being suspended between two languages is a dynamic and multi-layered, and sometimes frustrating experience. Neither completely here nor completely there, yet existence and meaning making is dependent upon on both.

* * *

Nazia Islam is a writer and artist from California. She is a Bengali folk culture enthusiast who enjoys learning about Baul music. Some of her visual poetry can be found on Instagram, and she writes at https://naztanu.wordpress.com/.