The word ‘Cliffhanger’ might well have entered the cinematic lexicon sometime toward end-1913, when early motion picture maker William Selig had a brainwave. His planned 13-part film-serial would appear simultaneously in movie theaters and newspapers, each two-reel episode ending on a suspenseful note, or poised on cliff-edge, to ensure sustained viewer/reader interest.

The Adventures of Kathlyn wasn’t the first serial to appear, or the first one that used the dual newspaper-film reel format. In 1912, the 12-reel What Happened to Mary by the Edison Company, had story-episodes in the Ladies World Magazine that coincided with a theater screening. In the silent film era, a reel corresponded to roughly 16 minutes.

Fathoming the East

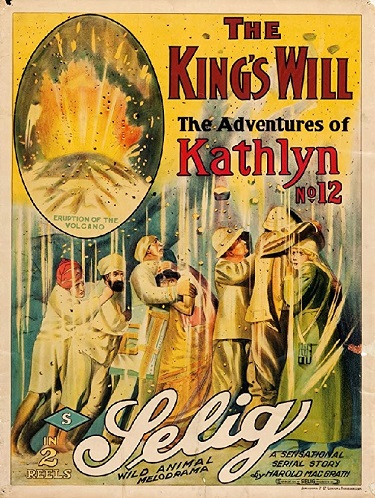

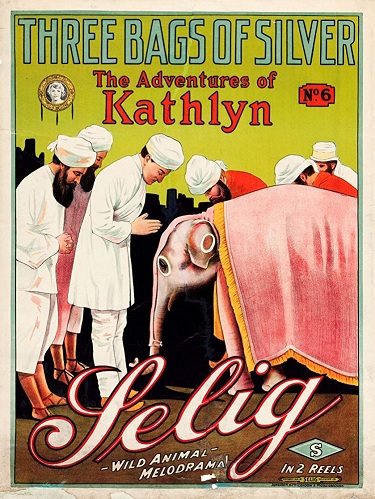

The Adventures of Kathlyn written by Harold MacGrath, was more ambitious, and besides its cliffhanger quality, had several things of note. Over six months — January to July 1914 — with fortnightly gaps between episodes, Adventures appeared in several newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune, and was released in theaters across most of the U.S. starting on December 29, 1913 by the Selig Polyscope Company.

Adventures was set in India, a country still largely unknown to the U.S. The land of “Hindus” (as South Asians were mistakenly called by most newspapers), the serial revealed an exotic, danger-filled East marked by almost every trope that would define the region for the next few decades: doddering maharajas, conniving princes, dense forests inhabited by all kinds of predatory animals, vast deserts, veiled women and people in thrall to gods, temples and priests.

The silent film actor, Kathlyn Williams, who played the fearless female lead, appeared on several occasions with a plethora of wild animals from Selig’s menagerie in Los Angeles. Animals, carnivores and dromedaries alike, featured in a big way in Adventures; lions and leopards appeared as fierce opponents and desperate predators, while elephants, camels and even a baboon served as key allies and helpful accomplices.

Selig’s Menagerie

Newspaper reports of the time mention how Kathlyn Williams, with some chutzpah, entered a cage with twenty lions; there’s no explanation if there was a protective net or any barrier, so one has to take century-old newspaper reporters at their word. The scar on her forehead was also attributed to a leopard, as Richard Abel writes in Menus for Hollywood: Newspapers and Emergence of American Film Culture 1913-1916.

Adventures provided William Selig (who prefixed a colonel to his name) a chance to make new beginnings. Selig, at first a roving magician, later had his own travelling vaudeville shows featuring Bert Williams and other African-American actors. Around the early 20th century, he was drawn to the world of making films, as new kinds of motion picture cameras and projectors came on the scene. At one time, he adapted one of Thomas Edison’s projectors (without paying the patent rights) to make his own short films. But the two — Edison and Selig — later reconciled.

Selig was perhaps the first to get into the “fake news” business when he made a film on Theodore Roosevelt in 1909. Soon after his term as U.S. president ended, Roosevelt decided to go big-game hunting in Africa. Selig asked permission for someone from the Selig Polyscope Company to accompany him, as photographer. But it was the Smithsonian, that published the National Geographic Magazine, that sent an English cameraman instead. Selig, unfazed by the rebuff, got together an actor (a Roosevelt lookalike), some animals from a struggling circus owner in Milwaukee, and made his own film showing Roosevelt in Africa.

Adventures in Allaha

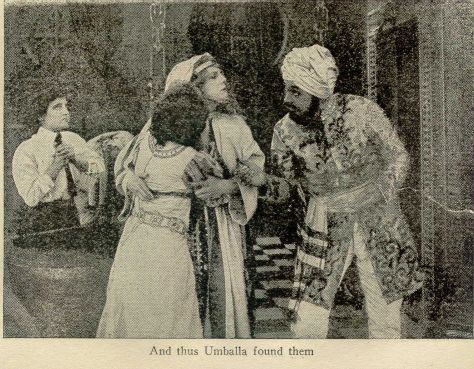

Adventures begins by Kathlyn making a clay model of an actual leopard. She leaves for Allaha, a small kingdom in India, to look for her father, Colonel Hare, a hunter who having saved the king’s life had secured the latter’s gratitude and been anointed successor. A decision that Prince Umballa, a rival for the throne, did not take too well, and Hare’s life was in evident danger.

Kathlyn encounters several dangers soon after she arrives. To get away from a forced marriage with Umballa, she has to prove herself in a faceoff against animals — a leopard and then lions. She is rescued in time by yet another American hunter, John Bruce, who conveniently happens to be in Allaha’s vicinity then.

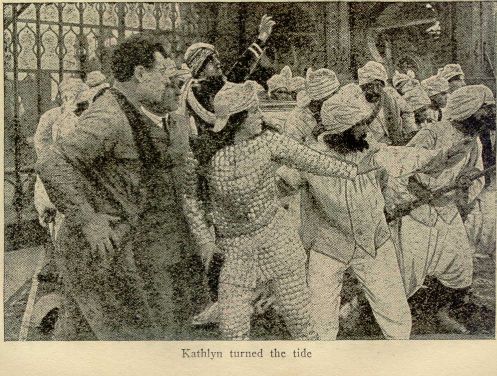

This presence of hunters in the film (Hare, and then Bruce) maybe be explained by how India, so soon after Roosevelt’s much publicized visit to Africa, appeared to most Americans as another extension of Africa; and thus a preferred destination for big-game hunters. Bruce appears in most episodes as Kathlyn’s rescuer — though she’s no damsel in distress. Considering that women in the U.S. didn’t have the vote then (national suffrage was secured in 1920), the silent films did give them — the independent-minded white women — a lot of agency.

Timely Escapes, Daring Rescues

Over successive episodes, Kathlyn has numerous escapes: on an elephant, from a sacrificial pyre and from a temple occupied by a lion. With Bruce, she ousts brigands out to steal a sacral elephant. She escapes slave catchers only to be sold as a slave to Umballa. She escapes prison by sending, via a baboon as willing accomplice, a message to Bruce.

Things get complicated with Winnie’s (Kathlyn’s sister) arrival in Allaha. It’s a place whose exact location in India appears uncertain but people from the West Coast of the U.S. seem to find Allaha easily enough. Kathlyn is recaptured again, while trying to rescue Winnie, and Umballa orders the two sisters to be fed to hungry lions.

Engineer Bruce constructs a makeshift tunnel to enable an escape. There is another capture, another devious torture plan by Umballa — this time Kathlyn is placed before a juggernaut impaled with stakes, and once again she’s saved, to lead a revolution dressed very much like Joan of Arc. Umballa escapes, and Kathryn learns of a treasure hidden on Volcanic Island. She braves raging seas, a suddenly eruptive volcano, a bridge that collapses providentially the very time a lion sets foot on it, and finds the treasure. Umballa is imprisoned and there’s a happy ending, especially for Kathlyn and Bruce, after all.

There were enough and more adventures to fill up 13 breath-taking, suspense-filled episodes. Adventures proved popular with most audiences, and the Chicago Tribune reported a ten percent rise in circulation. A complete novel appeared soon, available to read online here, and the longer silent film version followed in 1916.

A 13-minute clip from The Adventures of Kathlyn

Following The Adventure of Kathlyn, film serials like The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine appeared in the same format. Yet these were hardly part of the damsel-in-damsel genre movies that became such a staple in later years; as with Adventures, the female leads in Pauline and Elaine were resourceful and had plenty of pluck.

Brownface in Adventures & The Mysterious Hari Chund

The Adventures of Kathlyn had several brownface impersonations; Charles Clary played Prince Umballa. Horace (also called William) Carpenter was Ramabai — a noble disenchanted with Umballa and hence loyal to Kathlyn, and Goldie Colwell played his wife, Pundita. The real-life Pundita Ramabai, the social reformer, had indeed created a stir in the U.S. with her visit in the late 1880s.

There was, however, an actor who came all the way from India at Selig’s invitation. Hari Chund, as newspapers spell the name, or Hurri Tsingh, as he is credited, sailed with a cast of actors, lavish costumes and even camels, to help make the film. As was reported by the January 3, 1914, edition of the Houston Post, they sailed away (perhaps, without the camels) soon after the film’s completion.

Hari Chund, still a shadowy figure in film history, could arguably be the first Indian in a Los Angeles studio film; The Adventures of Kathlyn was entirely filmed in Selig’s studios at Edendale. More than a year later in 1915, Bhogwan Singh would appear in two short films produced by the Centaur Film Company, which had set up the first film studio in Hollywood.

* * *

Aditi Kay is a writer. Her novel, Emperor Chandragupta was published by Hachette India (2017) and will be available in an international edition in March 2019. She lives in New Jersey and works as a freelance editor and management consultant. Find her on Facebook.