Welcome back to The Aerogram Book Club, where editor Neelanjana Banerjee brings together writers and thinkers to discuss South Asian books of significance. Join in with your thoughts in the comments and on social media with the hashtag #Aerogram after reading the discussion of Seahorse with Banerjee and Monona Wali, a writer, filmmaker and screenwriter.

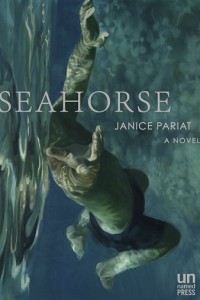

In Janice Pariat’s novel Seahorse, we meet Nehemiah — or Nem — a young man from Northeast India who is haunted by an intense love affair he had with Nicholas, a visiting art professor at his college in New Delhi. Years later, while Nem is living in London he thinks he is meeting Nicholas only to be reconnected with Myra, a woman he had been introduced to in India as Nicholas’s sister. We follow Nem as he immerses himself in these fluid and life-altering relationships and as he explores the culture of both New Delhi and London. A poet and a writer, Janice Pariat is the award-winning author of the short story collection Boats on Land (Random House India). Seahorse was recently published in the United States by Unnamed Press — a press dedicated to literature from around the world.

Neelanjana Banerjee: I think it is so interesting and crucial really, as a reader and writer, to read books written by writers from other parts of the world — whether they are written in English or in other languages. I think there is a different rhythm, a different sensibility that comes with this worldview, however subtle, and I really felt this while I was reading Seahorse. I wondered, Monona, if you felt this, too?

Neelanjana Banerjee: I think it is so interesting and crucial really, as a reader and writer, to read books written by writers from other parts of the world — whether they are written in English or in other languages. I think there is a different rhythm, a different sensibility that comes with this worldview, however subtle, and I really felt this while I was reading Seahorse. I wondered, Monona, if you felt this, too?

Seahorse is a moving novel about the way love can undo a person and also how it can reconstitute someone. Told from Nem’s point of view, the novel is constantly moving backwards and forwards in time, from the intense, underwater months that Nem and Nicholas spent in a lovely bungalow in New Delhi to present day London where Nem, older and more worldly, writes, goes to art shows, pubs and the theater with a bohemian group of friends — with the occasional hook-up thrown in. Then suddenly he reconnects with and visits Myra — a classical musician that is his sole connection to Nicholas. She lives deep into the English countryside, with her young son and curmudgeonly father.

The book is also filled with musings on love and time and death — as the novel’s inciting incident is the death of Nem’s friend Lenny, who was caught by his father having sex with another man and institutionalized. His death is ruled an accident, but Nem knows it for what it is — a suicide.

“Seahorse is a moving novel about the way love can undo a person and also how it can reconstitute someone.”

The book is a love story, and maybe that’s why I found it refreshing, because I couldn’t think of the last novel that I read that used love and erotic desire as its main conceit. And Pariat writes about both the emotional and physical aspects of love and desire beautifully, though often abstractly.

When Nem and Nicholas first consummate their relationship, she writes: “My fingers dug into his waist. He moved over me like a wave …. I shivered, arching, everything around me falling away, until all that was left was his closeness, no particular weight, no particular shape.” Another time, during one of Nem’s more casual encounters, “Then we scissored ourselves together, slick and moist.”

I was both enamored and sometimes irritated by Pariat’s erotic writing. It wasn’t as though she didn’t “go there” — what is happening between the characters is explicit, but they were etched in shadow. Sometimes I just wanted to turn on a very bright light and know exactly what was happening and who was doing what to whom. Not just because I like dirty writing (which, to be honest, I do), but because I think the power dynamics, the details of sex are so telling to the characters, to the story.

Anyway, I’m curious to hear your take on the sex, Monona, and which of the main characters in the book that Nem becomes obsessed with — Lenny, Nicholas, or Myra — that you thought was most fascinating.

Monona Wali: As soon as I entered this book I did feel I was in a different rhythm — a very poetic one. Nem’s voice is undeniably lyrical, wistful and melancholic. I liked being taken into the collegiate world in Delhi in a way that was contrary to all the stereotypes you hear about that world — the relentless competition, the vying for position and status — instead we get a picture of a kind of relaxed utopia of aesthetic exploration and a certain amount of degeneracy around drugs and drinking.

Monona Wali: As soon as I entered this book I did feel I was in a different rhythm — a very poetic one. Nem’s voice is undeniably lyrical, wistful and melancholic. I liked being taken into the collegiate world in Delhi in a way that was contrary to all the stereotypes you hear about that world — the relentless competition, the vying for position and status — instead we get a picture of a kind of relaxed utopia of aesthetic exploration and a certain amount of degeneracy around drugs and drinking.

It’s through the depiction of this world that we see how it offers Nem a refuge from his family within whose structure he cannot be himself — a young gay man who is not going to follow a traditional career path. By moving the location of the novel to London later in the story, we also get a portrait of a kind of international academic and artistic community in which Nem can find a home, even if it is somewhat makeshift.

I know what you mean about the abstract quality of the writing — and the descriptions of the sexual encounters were treated, I felt, the same way as all the emotional experiences that Nem has — kind of from an underwater perspective as you say, perhaps in keeping with the Seahorse theme. (Nem is fascinated by an aquarium that Nicholas keeps in his Delhi house, which is where he first encounters the seahorses.)

“One of the underlying themes was the role truth plays in the story”

There were several times when I did crave for Nem to come up for air — gasping, and sputtering. There are a couple of surprises in the book (without giving them away) and in those moments I really wanted the poetic varnish stripped off. One of the underlying themes was the role truth plays in the story — characters are hiding things from each other and when Nem discovers some of these shocking truths, I as the reader, wanted more of a reaction from him.

Of the three characters who are central to Nem’s life, I think Myra was the one who felt most real and embodied to me. We see her as a working musician, a mother, and a daughter, and so she feels like a living breathing human being. We never really meet Lenny since he’s part of Nem’s past, and the scenes with Nicholas in Delhi live in that kind of eroticized netherworld of first or second love. I actually found myself hoping things would work out for Nem and Myra. Of all the characters she seemed the most interested in Nem as a person.

Question for you — how did you feel about a woman writing about a gay man’s experience? Did it work for you?

NB: Thanks for asking that question, Monona, because it is definitely something that this book made me think about. Pariat has said that the novel is based on the myth of Poseidon and Pelops, the son of Tantalus, who was dismembered as an offering and then put back together by the Gods. When Poseidon saw how beautiful he was — this boy put back together — he stole him away to live with him under the sea and become his apprentice. I was not aware of this myth and missed any reference to it in the book besides a review blurb on the back, but I appreciate that it was Pariat’s launching point into this story.

NB: Thanks for asking that question, Monona, because it is definitely something that this book made me think about. Pariat has said that the novel is based on the myth of Poseidon and Pelops, the son of Tantalus, who was dismembered as an offering and then put back together by the Gods. When Poseidon saw how beautiful he was — this boy put back together — he stole him away to live with him under the sea and become his apprentice. I was not aware of this myth and missed any reference to it in the book besides a review blurb on the back, but I appreciate that it was Pariat’s launching point into this story.

I’ve been trying to think of any other novels I’ve read in which the protagonist is a gay, or bi-sexual, man and the author is a woman, and I can’t seem to find any. [I did come across much chatter on the internet about the prevalence of women writing “m/m” romance or fan fiction, which is a phenomenon unto itself.]

Like I said before, I liked Nem, and was immersed in his story, what did strike me was that Nem and Nicholas and Lenny, and later, another surprising character, are all dealing with homosexuality or queerness, but this idea is not really put into a larger context. Lenny’s death does linger over the whole novel, but how does that affect Nem? Is he ashamed of his own sexuality? What about Nicholas? Was there any fear that they would be found out?

In the world of the story, I believed the characters, understood their fluid sexuality, but wondered where they fit into a larger context of queerness both in the novel and in the larger world. In some way, I felt that the novel chose queerness as its subject, but also seemed to avoid it.

There is a small, ugly part of me — the MFA program robot brain — that thinks: “You CAN’T do this!” And again, that is why I enjoyed reading this book, because Pariat does it and I believed it. I believed Nem’s singular story. What do you think Monona? Did it work for you?

MW: Like you, my initial reaction was: Wait a minute! (Of course there is A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara — a huge current bestseller — also with gay protagonists.) I do think Pariat succeeded, and largely because the voice is poetic, and Nem is a character who is very in tune with his own surroundings, the natural world, and also with the nuances of his feelings. He lives in a world tinged with a heavy dose of sadness and loss.

MW: Like you, my initial reaction was: Wait a minute! (Of course there is A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara — a huge current bestseller — also with gay protagonists.) I do think Pariat succeeded, and largely because the voice is poetic, and Nem is a character who is very in tune with his own surroundings, the natural world, and also with the nuances of his feelings. He lives in a world tinged with a heavy dose of sadness and loss.

I have to say I really admire writers who make bold moves like this and are able to pull it off. I think of Claudia Rankine’s words on racial appropriation, on writing the “other.” She says the question isn’t so much do you have the right to do it, but why are you doing it?

“I really admire writers who make bold moves like this and are able to pull it off.”

In Janice Pariat’s case, I think there was a real empathy evident for Nem, an outsider to his own family, and then, more and more, an outsider to the English lover Nicholas, who abandons him with no explanation, who has lived a double life and never has to account for it.

I missed the references to the Poseidon/Pelops story also, but if I have to guess, I’d say that in a way Nem is rescued by Nicolas, the Poseidon of the story, who puts him back together from the pieces that Lenny’s death has left him in. Then, like in the Pelops myth, Nem goes off to ultimately win love for himself, but not without fighting a battle with the father of his love interest. I love stories that take myths for their underpinnings, and even if you have to go outside of the text to understand the references. (I do wish they weren’t quite so submerged.) I think Seahorse is a good and worthwhile read.

Pariat’s language, her fluid and masterful handling of time, and her international scope are all impressive. It’s a new voice, a really interesting one, and I’m going to be interested to see how Pariat continues to grow and develop as a novelist.

* * *

Read an excerpt of Seahorse online. Listen to the novel’s original sound track. To purchase a discounted copy use this link.

Monona Wali is a short story writer and novelist, and an award-winning documentary filmmaker and screenwriter. Her stories have been published in The Santa Monica Review, Stone Canoe, Tiferet, Catamaran, A Journal of South Asian American Literature and other literary journals. She teaches creative writing at Santa Monica College and volunteers with InsideOut Writers, an organization that offers writing classes for incarcerated youth.

Neelanjana Banerjee’s arts journalism has appeared in Colorlines, Fiction Writers Review, HTML Giant, Hyphen, New America Media and more. She is the managing editor of Kaya Press, an editor-at-large for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and teaches writing through Writing Workshops Los Angeles.