A conversation between Zain Alam, Dorothy Dhillonn, Bibi Dhillonn, Ravi Dhillonn, and Michelle Caswell. The original version of this conversation appeared in SAADA’s Tides magazine.

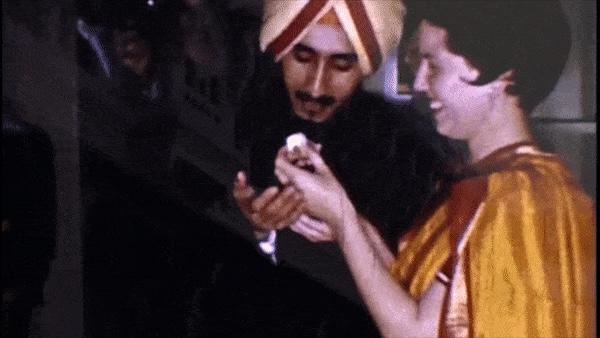

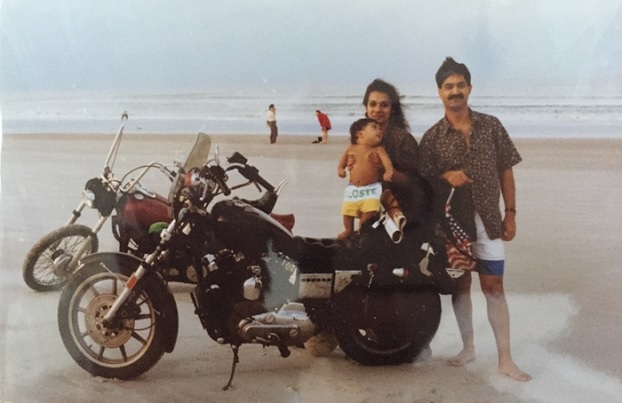

In 2017, the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) acquired digital copies of silent home movie footage donated by Bibi Dhillonn. Bibi’s father, Sharanjit Singh Dhillonn, came to the United States to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Oklahoma. In 1959, Sharanjit married Dorothy, a fellow student, in Norman, Oklahoma. Together, they raised four children, moving to North Edwards, and then later Lancaster, California, where Sharanjit’s job as a chemical engineer at Borax was based. The Dhillonn home movie footage documents their wedding ceremony, as well as provides an unprecedented glimpse into daily family life for South Asian Americans in the later 1950s and early 1960s.

“Through Lavaan, the artist puts Dhillonn’s historic home movies into conversation with the politics of daily life for South Asian Americans today.”

In 2017, SAADA received a grant from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage to launch a new project, Where We Belong: Artists in the Archives. As part of the project, five South Asian American Artists created new art reimagining historic materials in SAADA. One of the participating artists, Zain Alam (who performs as Humeysha), was inspired by the Dhillonn home movie footage to create Lavaan, a sound and video piece in which the artist not only created a score for Dhillonn’s silent footage, but remixed it with contemporary news coverage of anti-Sikh and anti-South Asian violence. Through Lavaan, the artist puts Dhillonn’s historic home movies into conversation with the politics of daily life for South Asian Americans today.

On March 8, 2019, SAADA co-founder Michelle Caswell facilitated a series of conversations with Dorothy Dhillonn (wife of the late Sharanjit Singh Dhillonn), Bibi Dhillonn and Ravi Dhillonn (the daughters of Dorothy and Sharanjit), and musician Zain Alam.

The text below has been lightly edited for length and clarity. A full transcript of the interview is available here. As a soundtrack to this interview, we offer a brand new four-part remix EP of Humeysha’s Departures. After premiering in 2018 on Stereogum, Departures has been reworked by collaborators such as Kurt Feldman of Ice Choir and ex-Pains of Being Pure at Heart, Myles Avery, as well as Humeysha’s own Dylan Bostick (Long Distance Call). Listen now and read on below:

Michelle: Bibi and Ravi, what was your reaction when you saw your family’s home movies for the first time?

Bibi: That was really emotional because I had no idea what was on them. I saw my grandmother, who I was really close to, but I didn’t even know we had any moving images of her. So it was a real shock and just really, really emotional to see her, but also to see my brother, because he passed away as well. It was really moving. I was so happy that we had these moving images of all of us in our old house. It was pretty exciting.

Ravi: I look at the footage and I think, who were these people? Their faces are so young and they look so different from the faces I remember growing up, there were smiles on them, not knowing what the future would hold. It’s incredible how beautiful they both are, a beautiful couple, with his turban and her sari. I was still surprised to hear my father’s voice and how happy he sounded. That’s not the father I knew; he was so serious, and so, so burdened down. And when I look at that early footage of us as kids, Bhagat and me playing, I realized that there was this happiness we had. We had a happy childhood for a while, you know?

Michelle: Did seeing the footage change how you think about your childhood?

Ravi: It does. Of course as you get older and you become an adult, you come to see your parents in a different way. But in looking at it as an outsider, I could just see them as this couple and knowing the history that I know, assess everything differently. It just allows a person to have a different perspective when you see the footage yourself. It’s a sort of disembodied kind of experience. I have felt different ever since I’ve looked at it. And I have to say also that watching the footage, initially just the silent footage, was one thing, but seeing it with Zain’s music and the political context and the artistry with which he edited it together, it brought tears to my eyes. I became very emotional and it was a completely different experience.

Dorothy: When I first saw Zain’s piece, I thought it was very nice. I appreciated it. I don’t think I had the same feelings Ravi did, but I really appreciated what it added to the footage. The whole piece brought it together, and he had a different outlook from what I did in my memory. It was interesting to see the way he put it together and, and there’s something about his music. It just evokes emotion.

Michelle: Zain, what was your reaction to seeing the footage for the first time?

Zain: You know, for me it was the same as what Bibi describes — the sense of joy and fulfillment and rediscovery. That’s the way I felt when I went to India the first time my senior year in undergrad, and began digging up these stories and writings and photos of my grandparents — and even of my parents when they were much younger and easily able to cross the India-Pakistan border. I think there’s a two-layered sense of how it’s really cool to find something personal that you feel connected to along with a lineage that you’re a part of. But those migration stories were fascinating in the longer historical trajectory too. In a similar way, when I came across the [Dhillonn] videos, it put a lot of things into perspective for me. I grew up in Kennesaw, Georgia post-9/11. Seeing the videos made me realize — not only are we not the first, but there were other people even deeper in the heartland of America who were having the experience of being American for the first time and asking, “Do we assimilate, do we integrate, do we resist?” It really put things into context, especially given what was happening politically at the time that I discovered the videos. So there’s such a long arc of history there, both personal and on a much larger scale.

Michelle: Zain, why did you choose to work with the Dhillonn home movies?

Zain: I remember when we began the fellowship and were just looking over the materials. At that moment I think I was talking to you guys a little bit about getting inspiration from some of the written pieces or the photos that were in the archive. But then I came across the Dhillonn video. There was just that initial, instinctual state of connection. Not only is this a story that I find fascinating, but there are the colors, the people, and the way I found them very beautiful and interesting to look at — both the family in Oklahoma and then the family that came to the wedding. There is just something aesthetically that I really loved about the texture of the materials that was unique amongst everything else I came across. It is strange to say, but it’s almost felt like a spiritual connection in a sense. Like whenever you’re going through materials, a big collection or archive, sometimes there is just that spark that emerges. In many ways it felt like a really natural fit from the beginning.

Michelle: Bibi, what was your reaction to seeing Lavaan for the first time?

Bibi: I’m probably going to get emotional talking about it, so get ready. It was just so beautiful seeing the moving images of my family with music and the superimposing of the images in the background. I don’t even really have the words. I’ve watched it again and again, and it just feels, you mentioned the word spiritual. There’s something deeply, deeply inside me that got moved by watching it. I shared it on Facebook because I wanted my family and friends to see it. I’m so excited about it and I’ve watched it so many times and every single time I’m so moved by it. I can hear the sound in my head because I’ve heard the audio so many times too. I never get tired of watching it. The music is really beautiful.

“I’ve watched it again and again, and it just feels, you mentioned the word spiritual. There’s something deeply, deeply inside me that got moved by watching it.” — Bibi Dhillonn

Zain: I was wondering, Ravi — earlier you mentioned the word disembodiment to describe when you were initially seeing some of this footage from your personal archives. My interpretation and reimagination of all that material — how did that affect you, and that feeling you described as disembodiment?

Ravi: Well, the politicization [of the news footage in Lavaan] produced the very opposite feeling. I felt it was closer to home. I felt it was more personal. That disembodiment feeling of seeing myself as a little kid, it felt like I was looking at a stranger, you know, the same way I felt when I was looking at the faces of my parents when I was seeing the wedding footage, if felt like, who are these people? We were not strangers but it felt like looking at strangers. You walk along through life and you think you know this person, you know these people, and then you see this footage and that changes, especially, with the backdrop of music, which of course is very emotional, especially your music, that particular piece. It changes your view.

Zain: When I was cutting it, I was thinking about your family in general. When I got towards the end of the piece, when it addresses the contemporary moment, I definitely wondered, as somebody who is not of Sikh background, as somebody who is not Punjabi, and somebody who has not grown up in the Midwest: is this going to affect people emotionally in a way that feels bad? Is it something that feels disrespectful to the traditions or to the communities?… But I also think there are two different things: the intellectual, self-critical, judgment-based mind and the aesthetic, creative mind. They shouldn’t be jumbled into one another and, in terms of process, they definitely should not be a tangled in with one another. But that also doesn’t mean that they should be a mutually exclusive part of the process.

“I’m going to simmer on it for as long as I can and really try to just see how this video speaks to me, what it’s telling to me.” — Zain Alam

I think a lot of times when there’s conversations about appropriation, or about stepping outside of one’s traditions, it tends to fall along one of those lines and in a very simplistic way. So for me, it was like — look, I feel like I found something beautiful, and I’m really going to go as far as I can to dedicate myself to just sitting with this material for a long time. I’m going to simmer on it for as long as I can and really try to just see how this video speaks to me, what it’s telling to me. And then accordingly build a world out of all that, that first and foremost, I find beautiful, that I find resonates with me and that hopefully through whatever creativity and sound I put to this, somebody else will be able to connect to it in a similar way, which perhaps might not necessarily be the case if they were just to see the full two hours of silent footage.

After we showed that video the first time [at the SAADA Where We Belong symposium], there was an elderly Sikh woman who came up to me and was also in tears. She was the first person who I had seen after we showed it. She had that emotional of a reaction to it. And in my mind, I immediately went to both of those parts of my brain, the judgmental part — oh my God, I really screwed something up. And then the other part of me–oh, no, she’s just really, deeply connecting to it. And the same way that I felt when I first encountered the material, these two parts of my brain, of our brains as human beings, don’t need to be mutually exclusive. There’s a degree to which these kind of questions are always going to be an art and not a science. I don’t want us to ever lose the magic of that.

Michelle: Prior to Bibi giving digital copies of the home movies to SAADA, have you ever thought about your family’s story as being history, as being important to people outside of your family?

Dorothy: No.

Ravi: I have. I’ve written bits and pieces of it through my whole life. Our stories are in the end, all we have, really, of ourselves. Take away all the material things, and we have our stories. I think it’s a very important for us to understand where we came from, what things were like then, different historical contexts, and why people behaved in certain ways, in certain contexts and, and how it’s different now.

Michelle: It’s amazing to me what this record is enabling. That footage is an object and a digital object now. But what’s most important is that it is enabling conversations and connections between people that weren’t there before. That makes the job of an archivist worthwhile.

Zain: As a musician, we have a very common practice of remixing one song into another. And I just really latched onto this word you used, disembodiment, because sometimes when I hear my own voice or my songs remixed by somebody else, initially I get that feeling of disembodiment, in which I feel — oh my God, I never would have heard my voice this way or I never would have pitched it up and down. But then after a while, you figure out that it is able to take on a new life in this other world that somebody else has invented. There’s almost a kind of re-embodiment. There’s a new life that my voice has been able to take on in someone else’s work. I was wondering if you had a similar feeling when seeing how this footage that you’re in — that your father and your father’s friend had created — was put into service. I have this vision of my own that I had with the piece.

Ravi: I had a professor who said in writing class that once you put that poem out there, it’s no longer yours. It doesn’t belong to you anymore. Now it’s everybody else’s.

“Seeing it as new is really beautiful.” — Ravi Dhillonn

I’m so glad that [Lavaan] is out there and that people are interested because otherwise it would be such a waste. And I feel like there’s so much more. We could talk for days. And I think that’s why it’s important to stay truthful about [our stories]. Whether it’s video, whether it’s music, whether it’s art [being produced with the original material], it’s not taking any of the truth away, or the originality away, it’s just looking at it from a new perspective and seeing that old footage in the context of today. Seeing it as new is really beautiful.

Zain: I also felt similarly when I first encountered the footage. I felt that I was almost seeing the history of South Asians and the story of South Asians in America completely differently by virtue of the fact that your videos and your family’s story push the timeline back a decade from what I had imagined. I think this exchange — both the one we’re having, as well as the exchange of archival material, the reuse of the old, putting the old into conversation with the new, to exchange and to interact and to engage in a conversation — we’re almost able to see ourselves in new light, despite differences of time and space. What more can you ask for?

***

Michelle Caswell is the co-founder of SAADA and an associate professor of archival studies in the department of information studies at UCLA.