Nusret Gökçe, aka #SaltBae, has given new meaning to the phrase “food porn.” The Turkish butcher and restauranteur recently took the internet by storm with his style and slices of meat.

Just 48 hours after Gökçe posted a video of his unique salting techniques to Instagram, it gained over 2 million views. Gökçe’s fashion, finesse, and passion for meat has spawned numerous copycats in a matter of days. No one, however, seems to do justice to the original.

Yet, he is not the only foreigner in recent memory to capture the world’s attention and appetite. Just months before Gökçe’s viral stardom, Arshad Khan sparked the curiosity of millions after a stranger clicked his photo at the Pakistani tea stall where he worked. In no time, Chaiwala, as he has come to be called, was modeling his good looks on morning talk shows, music videos, and advertisements.

‘Chaiwala’ gets modeling opportunities abroad https://t.co/QDcHROiC8q pic.twitter.com/TQsd3AIxCF

— Tribune Life & Style (@ETLifeandStyle) January 26, 2017

On one hand, Gökçe’s flashy entrepreneur-meets-icon demeanor could not be more different than Khan’s shy, unassuming personality. Where one confidently flaunts style and salted meat, the other still seems to be recovering from the shock of his unexpected success.

“The internet’s fascination with these men calls for a closer look into our assumptions of food, sexuality and class.”

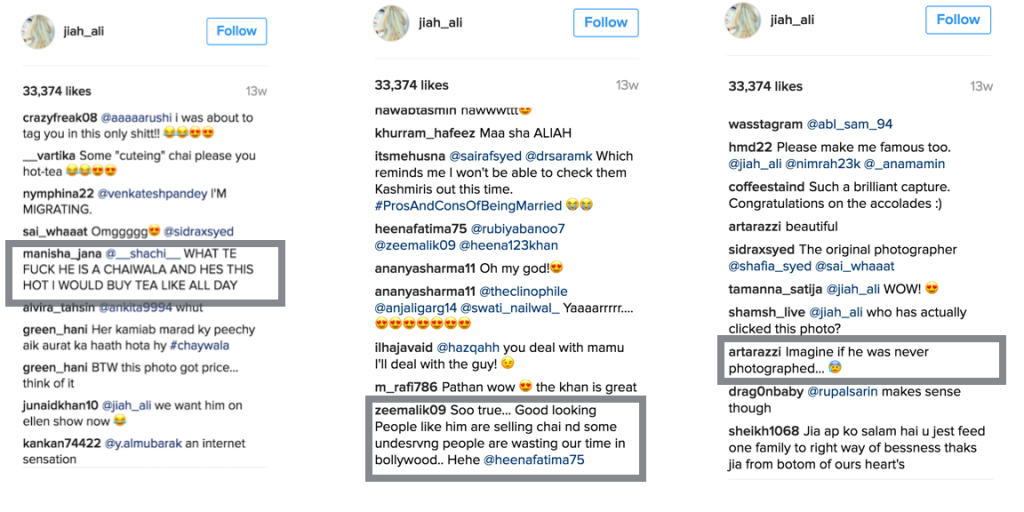

On the other hand, the internet’s fascination with these men calls for a closer look into our assumptions of food, sexuality and class. Surveying the tens of thousands of comments on their respective Instagram posts, fan reactions to both men range from various degrees of disbelief. On photographer Jiah Ali’s original post of Khan, one user exclaimed “WHAT TE [sic] FUCK HE IS A CHAIWALA.” “Good looking People like him are selling chai nd some underservng [sic] people are wasting our time in bollywood,” another lamented.

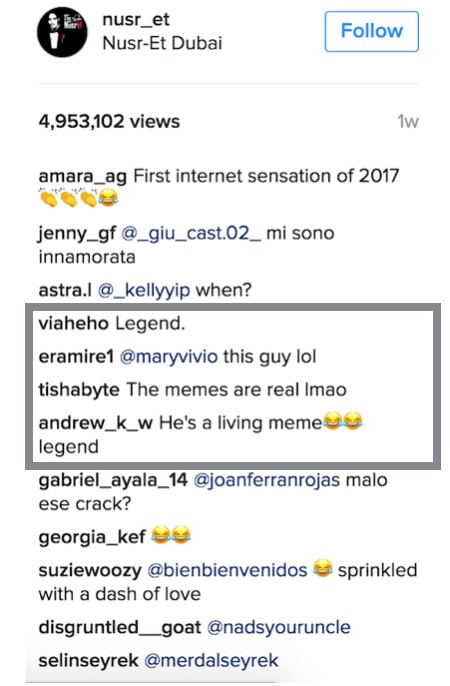

Other commentators remarked at Gökçe and Khan’s luck at being rescued from oblivion. Had they had not received this attention, fans wondered what their futures could have been.

In both cases, Gökçe and Khan are revered for their instant value as memes. As if this is what they were always meant to be.

Although these comments are meant to show appreciation, their collective shock and awe ultimately aims to ridicule Gökçe and Khan’s infamy. It is assumed that a chaiwala and a butcher are the last people who should exhibit such natural beauty and glamour. Compounded onto this is the fact that both men hail from countries that fall outside of the normal purview of their audience’s imagination. Their subsequent ‘memeability’ aims to highlight this disconnect between lowly laborer and exotic fantasy.

Gökçe and Khan’s rise to Internet fame demonstrate a classic example of the West’s Orientalist gaze. In his book, Orientalism, Edward Said traces the mythology of ‘the Orient’ as the exotic, inferior counterpart to the West. Due to the connective nature of social media, the West and the East may not seem as polarized as Said imagined them to be decades ago. Indeed, part of a meme’s success derives from a viewer’s ability to establish an intimate and immediate familiarity with the image at hand.

“Due to the connective nature of social media, the West and the East may not seem as polarized as Said imagined them to be decades ago.”

However, this does not diminish the function of the Orientalist gaze. Gökçe and Khan’s viral success is founded on the disbelief of their very existence. Although both men are ‘rescued’ out of obscurity, they remain trapped as ‘the Other.’ Due to the limits of the Western gaze, beauty and fashion are the only ways through which we relate to these men. As a result, Gökçe and Khan are not only objectified, but exoticized, as well.

In addition to these Orientalist tropes, issues of food and class further color our perception of these men. We find ourselves asking, “How can a hot guy be a chaiwala?” or “Why would a butcher of all people look like that?”, as if anyone could survive based solely on their good looks.

Negative perceptions of food service workers are rampant in the Internet’s fascination with Gökçe and Khan, despite their distinct socio-economic backgrounds. While Khan worked a low-income job at a tea stall, Gökçe is the successful owner of a chain of steakhouses. Despite his commercial success, reactions to Gökçe’s flamboyant butchery can be seen as emblematic of how many Westerners believe food service workers should act. We are as accustomed to our chai being served silently as we expect our meat to be cut without fanfare.

Yet, Gökçe and Khan are merely two examples of this trend. Shortly after #Chaiwala went viral, Kusum Shrestha was spotted selling vegetables in Nepal. #Tharkaliwali (“Vegetable Girl”) took off as the next South Asian sensation. Once again, admirers marveled at another chance discovery of natural beauty. Like Khan, Shresta was soon offered modeling and film contracts. Her luck was changed forever. After all, this is what social media was made for.

Here Comes Beautiful #Tarkariwali From #Nepal. Thanks To Social Media For All These 🙂 https://t.co/vuhAXJBYKI pic.twitter.com/YggdDZ6KjZ — Gundruk Post (@GundrukPost) October 29, 2016

Despite social media’s ability to make the world seem smaller, these stories of viral success demonstrate the pervasiveness of deeply entrenched stereotypes and assumptions. We welcome viral celebrities like Gökçe, Khan, and Shresta in an attempt to uncover hidden gems that would otherwise go unseen. However, the power of this gaze has the ability to do more harm than good.

“These stories of viral success demonstrate the pervasiveness of deeply entrenched stereotypes and assumptions.”

Although Gökçe, Khan, and Shresta will inevitably benefit financially from their internet fame, their stories are seen through a limited, Orientalist and elitist gaze. While these individuals have catapulted to fame, their “memefication” has done little to humanize service workers. Instead, they serve as exceptional eye candy to be rescued from their dull lives and, ultimately, consumed.

* * *

Salwa Tareen is a graduate student at Harvard Divinity School studying religion and politics in South Asia. Through her work, she seeks to explore the intersections of language, identity, and power whether in the form of poetry, dialogue, or academic research. She is also a contributor for Brown Girl Magazine. As a Pakistani-American woman born in Saudi Arabia and raised in Canada, in her spare time Salwa enjoys crafting clever quips to the question: “No, where are you really from?”

1 thought on “The Chaiwala, The Butcher & The Other: Food, Fetish, & Class Online”

Comments are closed.