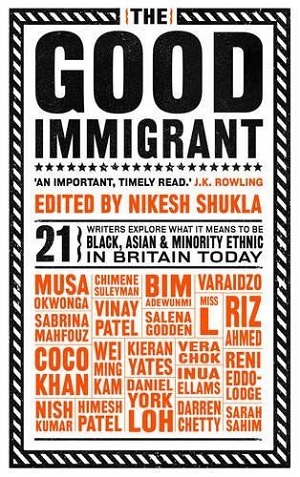

“BAME,” for those who may not know, is the acronym for “Black, Asian, minority ethnic” and used mostly in the U.K. And one of the most definitive books to have come out of the UK about the BAME experience is The Good Immigrant — an anthology of personal essays by creatives from across the spectrum about how their racial/ethnic identities have shaped their lives from an early age.

The collection is edited by the writer, Nikesh Shukla. In his introduction note, he describes how the book came about as a sort of response to a comment to a Guardian article, where the commenter was surprised that the journalist had picked writers of color to interview but not picked more “prominent authors.” Once again, it was a call for people of color to justify their seat at the table. In Shukla’s words, this book “collects 21 universal experiences: feelings of anger, displacement, defensiveness, curiosity, absurdity — we look at death, class, microaggression, popular culture, access, free movement, stake in society, lingual francas, masculinity, and more.”

The writers chosen here are, Shukla admits, people he knows and wanted to hear more from. So, yes, networks and nepotism have played a role. But those of us creatives who belong to minority groups know how these small networks are important and critical as support systems. And, to be fair, he has picked some good ‘uns. Let me throw out some names that a few popular culture fanatics ought to know: Riz Ahmed, Chimene Suleyman, Bim Adewunmi, Musa Okwonga, and, of course, Shukla himself, who is very active and vocal on both news and social media re. this topic.

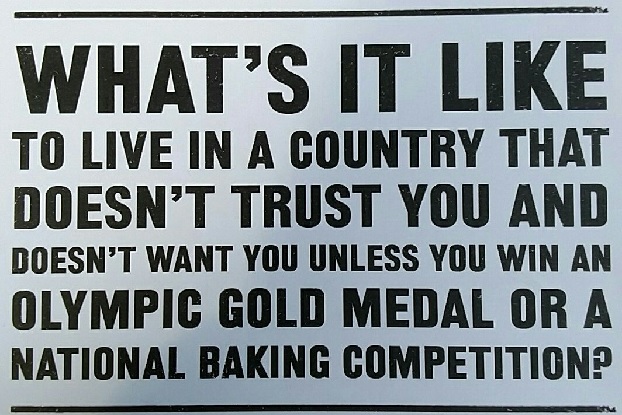

Describing how the title of the collection came about, Shukla writes:

Musa Okwonga, the poet, journalist and essayist whose powerful ‘The Ungrateful Country’ closes the book, once said to me that the biggest burden facing people of color in this country is that society deems us bad immigrants — job-stealers, benefit-scroungers, girlfriend-thieves, refugees — until we cross over in their consciousness, through popular culture, winning races, baking good cakes, being conscientious doctors, to become good immigrants. And we are so tired of that burden.

Some of these essays focus on the daily micro-inequities that people of color deal with so often that we do not think them remarkable at all. Till, of course, we sit down to consider what they actually mean in terms of how someone views us and what they might expect of us.

Vera Chok’s essay about being East Asian, for example, certainly made me reconsider my own attitudes and behaviors towards people from the East Asian community. This, despite having lived in the Bay Area for seven years, where there are significant numbers of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese people, and considering myself more “woke” than, say, some of my Midwestern friends (who, God bless them, would have a hard time differentiating between those ethnicities as if, as Chok remarks, yellow is “too pale a color” to be distinguished further.)

Actor Himesh Patel muses, in his piece, about whether he’s always been an outsider naturally, or whether being ostracized and othered from an early age has made him that way. He talks about how getting the role as a Pakistani Muslim on the long-running British soap, Eastenders, changed everything — especially as he is a Gujarati Hindu himself. The idea that “South Asian,” to many, meant that both were similar was initially disheartening to him. But then, after the Paris attacks, when one of his scenes of reading from the Quran struck a chord with many viewers, it brought home to him how storytelling is his way to promote understanding and tolerance.

Some essays take a more political stance about representation and personal agency. Darren Chetty writes about discovering, when teaching Year 2 kids in East London, how prejudices and biases set in early. Some of the kids, despite being from minority groups themselves, could not imagine or create stories with characters like themselves. All they had known were stories with white people.

Kieran Yates’ essay about going back to India was one I liked especially because I identified with the various experiences she described. The home country is also a foreign place for many immigrant or those born of immigrants and it takes some careful navigation to figure out how to assimilate back there, even on a short visit.

Sabrina Mahfouz, a woman of many ancestries, is predominantly of Egyptian descent. In her essay, she describes her love for ethnic headwear and her various experiences of how people react to those fashion choices. She goes deeper into where certain fashions in Britain and the rest of the Western world actually originated from — fascinating stuff when you start to think about it.

The pièce de résistance, for me, was Riz Ahmed’s essay about how he kept being stopped at airports for more rigorous immigration checks. It does not help that he plays on-screen characters that have, well, troubled histories. His writing is cinematic, in that he really takes you into the various interrogation scenes with him. And he remains, surprisingly witty and upbeat through it all. As for his big epiphany, part of it is as follows (but you should read the whole essay for the way he unpacks it):

You see, the pitfalls of the audition room and the airport interrogation room are the same. They are places where the threat of rejection is real. They’re also places where you’re reduced to your marketability or threat-level, where the length of your facial hair can be a deal breaker, where you are seen, and hence see yourself, in reductive labels — never as “just a bloke called Dave.” The post-9/11 necklace tightens around your neck.

Miss L’s essay about how, as a trained and accomplished actor, the roles coming her way are mostly those of “wife of the terrorist.” And as diminishing and demeaning as that kind of representation is, she does find the silver lining in it.

Sarah Sahim provides a historical introduction to Indian casteism but, like all the other essays here, she writes about much more than that. I am no stranger to this topic, having grown up in India till my late-teens. Yet, the way Sahim connects some of the dots between colonialism, casteism, and how neocolonialists would still have things the same old way, is rather interesting.

Bim Adewunmi goes into what is really meant by tokenism. And how, when people talk about wanting something “relatable” in books, TV, movies, music, they are really saying they want the default white experience. All representations of other cultures/people have to be earned, explained, deserved. The danger here is, as Adewunmi rightly points out, that if we cannot imagine people of color as superheroes, artists, scientists, lovers, etc., on our screens and in fiction, then we are even less likely to be open-minded to them when we encounter them in the street, the workplace, in our beds, in our lives.

Musa Okwonga gets the last word here in an essay that details his journey from humble beginnings to the privileged halls of elite private schools, Eton, and Oxford. He writes about how he felt an internal duty to disprove the widespread negative stereotypes of black people. Till he realized that even his best behavior would never really convince people of the contributions and larger good done by people from ethnic minority groups and he would always be expected to show his gratitude for the “chances” he had been given. Sadly, he decided to leave the United Kingdom and move to Berlin, Germany, where he found more tolerance for diversity.

A year ago a bunch of #thegoodimmigrant contributors came together to sign all the crowdfunder copies. <3<3 pic.twitter.com/W0sOAowZKh

— Nikesh Shukla (@nikeshshukla) August 24, 2017

This essay collection was released in September 2016, after the Brexit vote and its aftermath across Europe, and during the mad final stretch of the U.S. presidential election. It received glowing reviews from the likes of Zadie Smith and funding was received from the likes of J. K. Rowling. There have been, since, many similar essays from other BAME creatives across the Western hemisphere as our world continues to get more divided. A regular quarterly, The Good Journal, is also in the works. The question, though, is whether such books/essays are being read by those whom they seek to address? And will that make any difference?

In the meantime, of course, people of color should read these essays because they give unapologetic voice to our unspoken concerns, thoughts, and fears about our individual and collective places in society today. Culturally, professionally, and personally, we are all always looking for our identity anchors. But, more than that, we are also seeking our rightful spaces as effective and valued contributors.

* * *

Jenny Bhatt’s writing has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and the Best of the Net Anthology and has appeared or is upcoming in, among others: The Atlantic, Amazon’s Day One Literary Journal, Gravel Magazine, Lunch Ticket, Hofstra’s Windmill, Eleven Eleven Journal, Hot Metal Bridge, Vestal Review, Jet Fuel Review, Kweli Journal, Five:2:One, The Indian Quarterly, York Literary Review (UK), The Nottingham Review (UK), Litro UK, The Vignette Review, and an anthology, ‘Sulekha Select: The Indian Experience in a Connected World.’ Having lived and worked her way around India, England, Germany, Scotland, and various parts of the US, she now lives in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. She is currently looking for a home for her first short story collection. Find her at: http://indiatopia.com.