Kalpen Modi and I attended UCLA at the same time as undergraduates and were members of a progressive South Asian campus organization called Sangam. Kalpen ended up heading to Hollywood, where he is better known as Kal Penn. I went on to teach a course on South Asian American cinema at UCLA called “Harold and Kumar go to Westwood.” I named my class as a tribute to Kalpen, having seen him strive as he did for something he really believed in. As with many, I was surprised with Kalpen’s reaction to the legal decision on the New York “stop and frisk” laws but, also, because it seems to be far from how one who knew him in our college activist days would have thought he would have reacted.

Like Kalpen, I too have had the less than pleasant experience of being held up at gun point. But where his experience in D.C. was with a random stranger, mine was with the police in California.

* * *

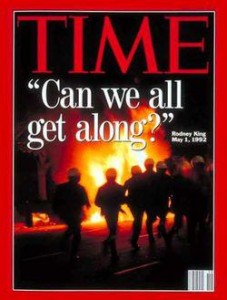

It was May 1992. Los Angeles was still on fire. Although the tumultuous scene was on our television set in India, it could not have felt any closer to home. The newscaster offered a recap of the story that my family had been following intently since April. Tensions had flared in the aftermath of the verdict in the Rodney King beating trial. [pullquote]And, like King, my first name is Rodney.[/pullquote]Despite videotaped evidence, the jury had exonerated the policemen responsible for violently assaulting the black motorist. The acquitted policemen, as well as the jury, had been all white. In a year, we would be emigrating to the United States. Los Angeles was our destination. And, like King, my first name is Rodney.

It was May 1992. Los Angeles was still on fire. Although the tumultuous scene was on our television set in India, it could not have felt any closer to home. The newscaster offered a recap of the story that my family had been following intently since April. Tensions had flared in the aftermath of the verdict in the Rodney King beating trial. [pullquote]And, like King, my first name is Rodney.[/pullquote]Despite videotaped evidence, the jury had exonerated the policemen responsible for violently assaulting the black motorist. The acquitted policemen, as well as the jury, had been all white. In a year, we would be emigrating to the United States. Los Angeles was our destination. And, like King, my first name is Rodney.

King was so much a part of my consciousness that I would often introduce myself as “Rodney … You know … like King? Rodney King?” I often needed the added qualification because, as I was told on more than one occasion, it was odd that someone of my racial background would have “a name like that.” As a teenager, newly immigrated to the States, my job at a fast food restaurant was my firsthand introduction to my new city’s racialization. In many ways, my workplace was a representative microcosm of Los Angeles — they were both equally diverse. Yet, what was plain to see was that while the staff at the restaurant were generally first generation immigrants, it was largely upper management and the clientele that were white.

During the unrest, when King famously made his televised plea for the people of his city to “get along,” his statement became the stuff of legendary ridicule. Was it that the notion of co-existing amicably was so simplistic, or that the sentiment had come from an ordinary black man with a rap sheet who had been beaten by the police? What the incident had done was to raise questions about police brutality and whose rights the keepers of the peace were protecting. For South Asians, among members of other ethnic communities, similar issues of racial profiling and civil rights violations rose to a crescendo in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks. Racial injustice may not be unique to any one minority group, but it is this very ubiquity of violence that should make us more mindful. Events in the current moment prove the need for us to voice our outrage, especially when it comes to those as defenseless as an ordinary, unarmed, young black boy whose life and rights seem to not matter at all.

Itself a legacy of the civil rights era, the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 aimed to disprivilege national origin in changing how immigrants would be allowed entry to the United States. Even in so doing, the express purpose of this change was to draw in highly skilled immigrant labor. The contemporary visibility of an upwardly mobile South Asian, and more specifically Indian, presence in America can be attributed to the 1965 measure. While 9/11 proved that class privilege was no deterrent to racial victimization, clearly, not all South Asians who immigrate to America do so from the technocratic ranks. Provisions made through family reunification clauses have diversified the community’s class demographics. In my family’s case, our petition for immigrant entry was made on the basis of my mother’s East African roots. As Goans of Kenyan heritage, despite the lack of quotas, it is evident that our case was helped because we were not only South Asian but also African — we ticked the diversity boxes for two developing regions.

[pullquote][…] America’s first black president — a man who, like me, had an East African history.[/pullquote]It is within these slippages of race and nationality that my personal experiences of being a dark-skinned resident of the United States have taken shape. The arrest occurred in January 2009. It had been a few short months after I had become an American citizen; short months after I participated in an election that brought to office America’s first black president — a man who, like me, had an East African history. Just off the bus from work, I was on foot, a few blocks away from my apartment in West Hollywood when a siren blared behind me. In broad daylight, I was handcuffed in my own neighborhood and shoved into the back seat of a deputy sheriff’s car. Citing a violation of the fourth amendment — which protects people from search and seizure without justifiable cause — I took my case to the ACLU, stating that I had been a victim of racial profiling. “What makes you think this was about race?” the lawyer had asked. “What would make me think it wasn’t?” I wanted to say, but was stopped from doing so because the case just was not high profile enough for the organization. Technically, I had not been arrested because I had not been brought to the station; never mind that one never forgets what a pair of cuffs feels like.

“Rodney, huh?” The officer was looking at my California ID while the cold steel continued to bite into my wrists. Upon finding my UCLA identity card, establishing that I was an instructor there, the officer’s tone changed dramatically. “The reason I stopped you,” he said while uncuffing me, “is because you resemble a man who committed a burglary in this area earlier today.” Leaving aside the ludicrousness of why someone would be traipsing about on a brightly lit sunny day just after they had perpetrated a crime, I got straight to the point and said, “You stopped me because you made an assumption about my race.” Inadvertently confirming my suspicion, the officer responded, “It doesn’t matter if you’re a black. All that matters is that you matched the description I have.”[pullquote]“You stopped me because you made an assumption about my race.”[/pullquote]

Was it because “a black” was in the wrong neighborhood? The irony should be apparent that in an area thought of as being liberal because of a large gay and lesbian presence, my complaint to the West Hollywood Sheriff’s Department was met with the party line that, after an internal investigation, it was ascertained the officer had acted in accordance with policies and no evidence of racial profiling could be found. I am sure it was also not racial profiling when a San Mateo policeman stopped me for questioning in September 2011 claiming that I resembled a criminal. “I’ll show you what I mean,” the officer said, producing an image. “You have the same eyebrows,” he explained helpfully. It was probably also not racial profiling when I was questioned extensively at airport immigration in September 2001.

In spite of my name, my dark skin, and my African history, unlike Rodney King, I have the “privilege” of proving that I am not African American. “Long after your case is closed, you are going to have to be Rodney King for the rest of your life. Do you think you can handle that?” attorney Steven Lerman had asked his client, the Los Angeles Times reported in a story following King’s death last year. “Steve, I just don’t know,” King replied. The same article quotes an earlier interview in which King had mused, “People look at me like I should have been like Malcolm X or Martin Luther King or Rosa Parks. I should have seen life like that and stay out of trouble … But it’s hard to live up to some people’s expectations, which [I] wasn’t cut out to be.” King was an ordinary man upon whom national attention had been thrust without him having asked for it. As I mourn the miscarriage of justice in the Trayvon Martin case, I am reminded of an ordinary King. These are the legacies that remind us that injustice is all the greater because of its ordinariness, and all the more ordinary when one is black.

Earlier versions of this essay appear on the author’s website and in this month’s issue of India Currents.

R. Benedito Ferrão splits his time between north London, northern California, and north Goa. In addition to teaching courses on film and literature, his writing on diaspora and public culture has been published internationally. Find his blog at thenightchild.blogspot.com and on Facebook at The Nightchild Nexus.