I’ll never forget that warm August day in 2008 — I had just moved into my first apartment, and my new neighbors had invited me and my roommates over for lunch. After a pleasant afternoon of chatting and eating, I was stepping out of their apartment when I heard that horrible call that every South Asian-American has known for over 20 years — “Thank you, come again” in an atrocious fake Indian accent. Apu had struck again.

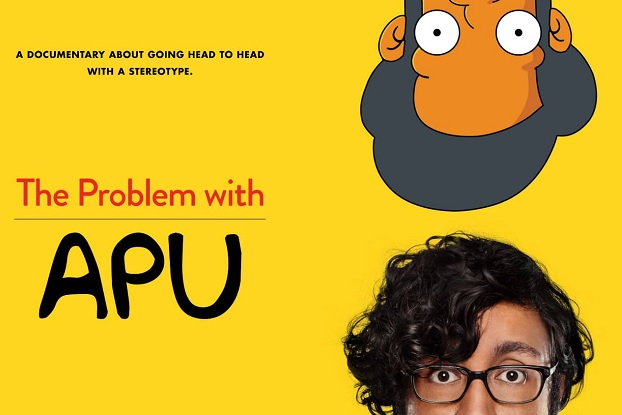

I’m not the only South Asian American Apu has been haunting, either; comedian Hari Kondabolu is so displeased by the character, that he made a documentary, The Problem With Apu, released on TruTV in late 2017. In it, Kondabolu speaks to several prominent South Asians — from comedian Aparna Nancherla and actor Utkarsh Ambudkar, of Pitch Perfect fame, to former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy. These South Asians occupy different niches in our culture, but they are bound by a common thread — having been bullied with “Apu” jokes in their past.

“…they are bound by a common thread — having been bullied with ‘Apu’ jokes in their past.”

The documentary opens with a brief introduction to Apu Nahasapeemapetilon: he is a resident of Springfield, along with the Simpsons, Mr. Burns, and the rest of the cast. He operates the Kwik-E-Mart, is often the voice of reason in Springfield, and has a ridiculous “Indian” accent. That’s it. What little backstory he has makes a punchline of his Indian heritage — his arranged marriage to wife Manjula, his numerous children — emphasizing to the viewer that it is nothing about Apu, only his existence, that deserves the viewer’s ridicule.

The salt in this Apu-shaped wound, Kondabolu explains, is that the character is voiced by Hank Azaria, a white man. Azaria has voiced a number of characters on The Simpsons, and is renowned for his work — so how did the insensitivity of the overly emphasized accent (known as patanking in the industry) escape his notice?

The film shares a clip of Azaria in an interview, in which he explains that the producers asked him to make Apu’s voice as stereotypical as he possibly could — offensiveness be damned. But in a clip from an interview with show producer Mike Reiss, we learn that the Kwik-E-Mart clerk wasn’t meant to be South Asian; instead Azaria added the accent in a script read-through for comic effect, and it stuck. And so, Kondabolu introduces the central aim of his quest: to speak to Hank Azaria and get to the bottom of the story of Apu.

Azaria’s role in Apu’s character, however, brings Kondabolu to his next main point — was Apu a cartoon version of brownface? To address this issue, he speaks to Whoopi Goldberg, who discusses an interesting theory: Apu may be a modern minstrel. She goes through the history of minstrels; how African Americans were perceived in popular culture as so subhuman that the act of putting on blackface was seen as comedy in itself.

“…was Apu a cartoon version of brownface?”

Minstrels were living caricatures of real people, with real stories, reduced to nothing more than a punchline and given no agency in their own perception. Apu’s story follows this exact narrative; as a character created and voiced by white folks, he creates a perception of South Asians in popular culture that is devoid of nuance or empathy, and serves to highlight his — and by proxy all South Asians’ — otherness.

Though Kondabolu’s academic approach to The Problem with Apu makes it a compelling watch, perhaps the most emotionally effective portion of the documentary is when he speaks to his parents about their feelings regarding Apu. They came to the U.S. from India several decades ago and made a life for themselves in New York. They had children and worked hard to raise a family in America, despite the hardships they faced.

In an aside with Canadian comedian Russell Peters, we learn just how difficult it could be for their generation of immigrants in decades past; Peters mentions that his father, who had a degree in English, would often apply for jobs in his field, only to be told that the position had been filled once the interviewers met him in person. In those days, microaggressions were the least of these Desi Americans’ worries; institutionalized racism that prevented them from getting jobs, housing, and other opportunities were overt. Perhaps worst of all, the early 1980s saw the rise of the “Dotbusters” hate movement on the East Coast, which threatened South Asians with vandalism, destruction of property, and physical violence. The police did little to help.

“Their accent, their culture, their religion, everything they held dear was just a joke, undeserving of respect.”

Despite this adversity, these immigrant parents persisted. They worked hard to create opportunities for themselves, developed community, and raised families, often on very limited budgets. And so, Apu’s character, who is meant to represent Kondabolu’s parents, Peters’ parents, my own parents, the parents of every first-generation South Asian American — is the ultimate insult; it taught mainstream America they were something to be laughed at, instead of respecting the South Asian community’s achievements or fighting against the violence and systemic injustice they faced. Their accent, their culture, their religion, everything they held dear was just a joke, undeserving of respect.

This exploration brings the documentary to its thesis point, of sorts — for years, The Simpsons creators have said that their portrayal of a variety of minority groups has been fair, since everyone gets ridiculed equally. The problem with Apu, then, is that for many South Asians, that was the only representation of ourselves we saw on screen, and we had no part in creating or maintaining it. In a darkly hilarious scene, Kondabolu sits in a room filled with contemporary South Asian TV and film stars, and asks them to raise their hands if “Apu” had ever been used as a slur against them. Nearly every hand went up.

At its core, Apu’s character deprived the Desi American community of being able to define itself in America. As the South Asian American population was rising in the late 1980s, The Simpsons came along and became a runaway hit — and essentially told mainstream America how they should feel about them. Because the show was such a cultural giant, it did not allow for South Asian Americans to define ourselves; a fact to which showrunners appear to be blissfully unaware.

When asked, point-blank by Kondabolu if the show’s producers had ever considered Apu’s repercussions on the perception of South Asians in America, most of the interviewees stared back blankly. It was clear that they cared so little, that the cultural consequences of the character they created had not even crossed their minds.

Ultimately, Kondabolu was not able to speak to Azaria in person about his problems with Apu. In an email exchange, Azaria explains that he is “uncomfortable” with the idea of being put on the spot; being at the mercy of Kondabolu’s editing seemed to make him nervous about the light in which the documentary would cast him. This, the film explains, is the crux of the privilege.

“The problem with Apu, then, is that for many South Asians, that was the only representation of ourselves we saw on screen, and we had no part in creating or maintaining it.”

Azaria is able to deny Kondabolu an interview to protect his public perception; this is not something that South Asians were ever able to do because of Azaria’s portrayal of the character, and by extension, the entire Desi community. Although Kondabolu deemed his quest a failure, the irony of Azaria’s rejection served to vindicate the premise of the entire project: it was time for the South Asian perspective to be heard, regardless of how The Simpsons showrunners felt about it.

Perhaps it was my early experience with Apu-related bullying that prevented me from taking a critical eye to the issue. All I knew was that the character made me angry, without really thinking about why. However, watching The Problem with Apu, I was able to take a step back and really examine this issue.

It showed me and other viewers that we were not alone in our annoyance; Apu Nahasapeemapetilon has been a specter in the lives of Desi Americans for the last 30 years. The Problem with Apu is important (not to mention entertaining) for everyone, to better understand how the insidious effects of lack of representation in popular culture can affect entire generations of people.

***

Rashmi Venkatesh is a pharmacologist who now works behind a desk and lives in the Metro D.C. area. Her interests include feminism, pop science, South Asian diasporic culture and media, and biryani. You can find her on Twitter at @rashmiv11.