South Asian Americans walk a particularly narrow tightrope as working professionals in America. Classified as the quintessential model minorities — intelligent, hard-working and non-troublesome, they have enjoyed outward indicators of success. Indian-Americans in particular, have the highest household income of any other Asian American group in America. Yet despite the high education, the wealth, and the apparent upward mobility, South Asian Americans — especially women — are noticeably absent from leadership roles in America.

It’s important to note the lack of South Asian American-specific data; data on Asian Americans typically aggregates all Asian subgroups en masse, which results in less valuable insights. The Asian American and Pacific Islanders Institute encourages schools to disaggregate data on Asian students (here’s why) but most school systems do not yet do this. The term “Asian-American” is largely unhelpful as it broadly categorizes Americans with roots in over 23 countries and at least 100 languages.

“South Asian Americans — especially women — are noticeably absent from leadership roles in America.”

Even so, available research provides important insight into some of what holds South Asian Americans from reaching the highest levels of American workplaces today.

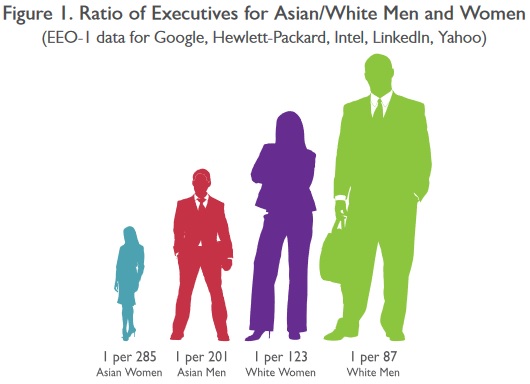

The Ascend Foundation, an organization dedicated to developing pan-Asian leaders finds: “Asian American men lag men of all other races and Asian American women lag women of all other races in reaching executive levels,” concluding that race had a significantly larger impact on professional advancement in America than gender. One study found when identical emails were sent out to professors at American universities, the recipients were overwhelmingly more likely to respond to white male students than students of any other race.

Hiring South Asian Americans seems to offer organizations the advantage of visible diversity. South Asian American professionals we surveyed for this article described benefiting from corporate pushes for diversity: “people think I add ‘diversity’ without being ‘threatening,’” shared one respondent. Added another: “It’s never been overtly stated, but I assume certain opportunities…were made available to me because I would bring a brown body to the table. Yet, these ‘privileges’ are only extended to a certain level.”

“It seems being Asian American may get your foot in the door, but it creates a whole new ceiling.”

Still, while hiring South Asian Americans seems to let companies check off their diversity box, they still overlook these hires when it comes time to promote people. In our survey for this article, one South Asian American said a white coworker with less experience was promoted instead of them for no identifiable reason. To add insult to injury, one respondent reported actually being fired for being too quiet — which their boss perceived as “intimidating,” while another was told she was “too blunt” and “needs to learn how to say no differently.”

One report finds that only 1 out of 285 Asian women in Silicon Valley is an executive. It seems being Asian American may get your foot in the door, but it creates a whole new ceiling. In fact, Jane Hyun wrote an entire book, Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling, about the many challenges Asian Americans face in attaining leadership positions, including biases managers hold against their ability to lead effectively.

The difficulties South Asian Americans face in progressing within our workplaces can be traced back to classrooms, where most teachers also believe the model minority myth, and treat students in a way that reflects that perception. A majority of surveyed South Asian Americans report having support needs that went unmet by teachers. It can be downright dangerous if a child has special needs that go overlooked, or when teachers ignore children who need more support than the average student, because of model minority stereotypes.

In reality, most South Asian Americans don’t fit the model minority stereotype. The authors of Adolescent Diversity in Ethnic, Economic and Cultural Contexts argue that not only does literature debunk the model minority perspective, but that Asian American adolescents may actually face many significant challenges. These include a struggle with their ethnic identities — Asian American teens have the lowest ethnic pride of any minority group — and facing stress tied to “trying to meet academic expectations.” They also found girls from Asian backgrounds have the lowest self-esteem of any minority adolescent group, and that while Asian Americans are perceived as psychologically well-adjusted — because of being successful model minorities — they have the same, and sometimes higher, rates of mental health problems relative to white Americans.

“In reality, most South Asian Americans don’t fit the model minority stereotype.”

Plus, South Asian Americans might not always even be as “successful” as people think. In a recent study looking at the historical and sociological contexts of South Asian immigration, researchers found South Asians actually have highly varied levels of education attainment and economic success; occupational trends for South Asian Americans are bimodal, and many work in lower-wage occupations.

Still, it can be easy to think the stereotype is innocuous in the long term. Perhaps it could play out as a kind of positive self-fulfilling prophecy (like the famous 1968 Pygmalion study, which found students made greater intellectual gains than their peers, when their teachers believed they would); kids do internalize the stories they’re told about themselves. But there are worse things a student could internalize about herself than that she’s a smart kid who works hard and doesn’t cause trouble — the model minority stereotype is a beneficial, positive stereotype, right?

But here’s how this plays out in reality: A South Asian American student in middle or high school, who is repeatedly treated as, and expected to behave as, a model minority, may identify as someone who works hard — but doesn’t speak her mind. She may meet the expectation that she stay out of trouble, but imagines herself as “rather dull on a personal level.” She may aspire to work for a great company, and might view herself as a great employee, but it may prevent her from aspiring to climb the career ladder. The stereotype leads her to place limitations on her own future, as much as the society around her does the same.

“The stereotype leads her to place limitations on her own future, as much as the society around her does the same.”

Students from all racial and cultural backgrounds, many of whom will someday become hiring managers and CEOs, are not immune to the effects of socially accepted stereotypes. They too, will internalize the view of their South Asian American classmates as good workers but not necessarily good leaders. Dismissing the seemingly innocuous effects of the model minority myth perpetuates institutions that allow South Asian Americans to progress… but just to a certain level.

It becomes incumbent upon educators first, to correct for this. Since existing data on Asian Americans suggests students broadly perform well academically, there is little motive for school systems to better understand these students. However, teachers must provide culturally responsive and sensitive support to all students — thus, the onus is on teachers to become more proficient in understanding South Asian American students’ cultures and experiences. Improving teachers’ culture specific literacy and proficiency is crucial if teachers are to create a supportive classroom environment for students of all backgrounds — one in which overt racism is certainly banned, but so is lighthearted mocking of cultural stereotypes and racial differences.

“Between 2000 and 2010, South Asian Americans were the fastest-growing major ethnic group in the country, and this trend is on track to continue.”

We find the pervasiveness of the model minority myth in the classroom often becomes the albatross that inhibits South Asian Americans from receiving the support so many of them may need as students. This then inhibits them from attaining the highest levels of success in the workplace.

American leaders and policymakers must take note of the South Asian American experience in schools and organizations. Between 2000 and 2010, South Asian Americans were the fastest-growing major ethnic group in the country, and this trend is on track to continue. When educators, leaders of school systems, and the education community at large misunderstand the diverse needs of South Asian Americans in the classroom, as well as their full potential as students and later, as professionals, this perpetuates systems that stifle the growth and success of a significant demographic of our population.

* * *

Dr. Punita Rice is an education researcher and director of ISAASE, an outreach and advocacy organization aimed at improving South Asian American students’ experiences in schools. She writes about her research and about motherhood and life on her blog at PunitaRice.com, and is writing a book about South Asian American experiences in schools (Lexington Publishing, forthcoming). Find her at @punitarice.

Ruchika Tulshyan is the author of ‘The Diversity Advantage: Fixing Gender Inequality In The Workplace.’ She is also an advisor, speaker and journalist who covers workplace equity and inclusion. Visit rtulshyan.com and connect with her at @rtulshyan.

Punita and Ruchika first got in touch with each other because of a piece Punita wrote for The Aerogram.