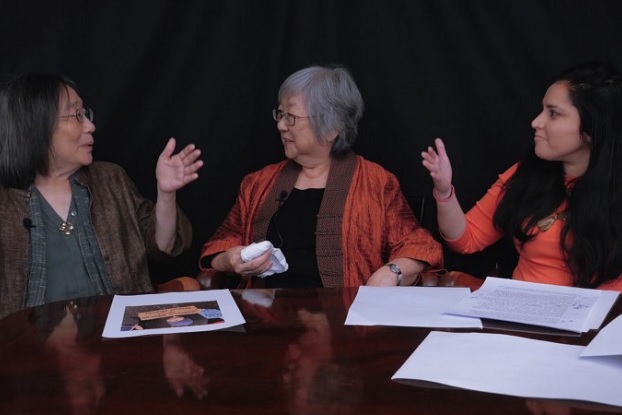

The Aerogram shares a condensed version below of Pia Sawhney’s conversation with Rosanna Yamagiwa Alfaro and Margaret Yamamoto. It was filmed in May 2017 in Concord, Massachusetts. Sawhney has also made available for reading online a longer version of this conversation.

* * *

It’s a grim year indeed. As Donald Trump’s insidious tweets and speeches roll on — his bluster, contempt, and prejudice show little sign of abating. As such, it is quickly becoming cause and reason to reflect on the past and consider historical moments that, although distinct from ours, still endure and resonate.

Playwright Rosanna Yamagiwa Alfaro and educator-activist Margaret (Margie) Yamamoto lived through World War II and the Japanese internment experience. They recently spoke with journalist Pia Sawhney on the art, activism and personal histories that have shaped their lives. Their Japanese American heritage has informed their caution and concern in the Trump era, especially, and both have actively protested the Muslim ban.

Rosanna has also written and produced two plays on Japanese internment. You can read one of them, “Don’t Fence Me In,” online for the first time here.

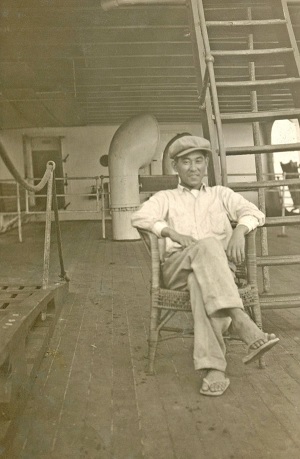

PS: So, 75 years ago [this year] Japanese Americans were interned, unable to leave the camps they were assigned to, surveilled constantly, had to bathe and eat collectively, and line up for filthy bathrooms. Two-thirds of those incarcerated were already American citizens. So, Rosanna, the genesis of this discussion, and you may or may not realize this, is this photo that you sent me in an email.

After the ban, there was talk of putting in place a Muslim registry. In fact, it started during the campaign but continued after Trump unveiled the ban. And it’s much like the one Roosevelt enacted, in fact, to require Japanese people to register with the Department of Justice in 1942, a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

PS: What’s the connection between Japanese Americans and Muslim Americans today? How would you make that connection? I say it because it may in some sense seem like a self-evident question. But I say it because, even in the South Asian community, there is a tendency for non-Muslims sometimes to say, well, you know, “I’m not Muslim. I may look like a Muslim but I’m not. I don’t want to be lumped in with Muslims because they appear to be disloyal and I don’t want to have the baggage of that associated with my identity.” How do you feel the Japanese American community has rallied on this, and why do they think this is so important?

MY: Well, for me it goes back to — do you remember when the Iranian hostages were taken, way back when? And I was in San Francisco at the time. And when that happened, there was a cry to deport all the Iranian students and anybody living in here who had a background. And every time something like that happens — it happened after 9/11, it’s happened now and every time it happens my first reaction, of course, is it’s horrible but my second reaction is, it’s happening again, what happened to us. I may have been two months old, but what happened affected my whole family and the way our lives went on after that.

And so, especially after 9/11 when I was here on the East Coast and I saw the reaction to it, and what was happening to South Asians. Being killed and murdered because of the fact that they wore a turban or something and talking to our South Asian friends who were not allowed to get on airplane flights.

PS: I was wondering if you could tell us about some of the work the Japanese American Citizens League did because you really managed to make some headway on rules that were repealed, the laws that were repealed.

MY: There’s some real interesting laws in our history. I, just, in doing a little bit of research found there was a law that said, if you were an American citizen, and married an Asian national, in our case, a Japanese national — Quite frankly, I don’t know if it was just for the Japanese or if it was all Asians — you lost your American citizenship.

I know the only reason I know about it is that a Japanese American woman worked to have it repealed. Because my mother was an American citizen and my father was a Japanese citizen.

(In March of 1907, Congress passed the Expatriation Act, which decreed that U.S. women who married non-citizens were no longer Americans. At the time, Asian immigrants were not considered racially eligible to naturalize. Then, in 1931, the Naturalization Act of 1906 amendment allowed women to retain their citizenship even after marrying Asians.)

PS: And your family, I mean, you mentioned your father came here as an illegal immigrant.

MY: Oh yeah. My father came in about 1925, when there was an Asian Exclusion Act in effect and no Asians were allowed to immigrate into America. And so, my father took a boat from Japan to Mexico and then he walked into California where his brother had previously immigrated. And he went with the Mexican migrant workers picking tomatoes and he could pass because he got tanned and he picked tomatoes with them all the way into LA, I guess. And then hooked up with my uncle and then stayed.

(Under the Immigration Act of 1924, also called the Johnson-Reed Act, the number of immigrants permitted to enter was limited through a national origins quota. But the act excluded all immigrants from Asia.)

PS: It’s interesting on the topic of illegal immigration because Trump was elected and even before Trump’s campaign, it seemed sensible to talk about legal immigration. It seemed like, you know, obviously everybody wants to come here and at some point, maybe there should be some parameters about who gets to come here and who doesn’t get to come here.

But after Trump started campaigning and really race-baiting and creating a sense that there was something unworthy about immigrant groups, about people who came from other places illegally, that there was something about their ethnicity that was the problem. That there was a need to create a whiter country, well, then we start asking, well, why should we make this compromise over legal immigrants? Why should we say, because if the idea is well, we’re trying to get to a whiter nation, there’s a moral obligation to say, well, I’m not going on that voyage with you.

Well, we might as well allow all immigrants, regardless of status, to come and to live here. And so, what do you think about that? Do you think it’s affected how you think about this? Or have you always felt the same way about legal versus illegal immigration?

MY: Well, right now, everything I’m hearing about how difficult it is to get into this country, from anybody, I’m not for that type of immigration. You know this is a question I haven’t really thought about, do I want wide open immigration or do I want somewhat controlled immigration?

Well, I guess, that is a very tough question to ask. I would think I would want some sort of control.

PS: Well, it’s the rationale, the rationale is also significant. And how you present the rationale is significant. That’s what I’m wondering, it’s one thing to say, well, we need parameters, we have limited resources and this kind of an argument. But if the argument is, well, we need to make the country whiter, well, suddenly the argument for legal immigration suddenly shrinks a bit.

MY: You say, wider or whiter?

PS: No, whiter with a ‘t’. You feel like you’re on some other journey, some trip you didn’t ask to join.

MY: Well, I’m not for the way it is now.

RYA: I’m certainly against any racial or religious restrictions. I went to the immigration rally in Copley Square and there were Muslim scientists carrying placards, you know, saying, “I am saving people from heart disease, I’m not a terrorist.” And that’s so obvious and it just breaks your heart to see something like that. And what kind of country are we going to be if you’re going to deny all these people who’re doing so much good just because of the way they look.

PS: Immigration is already complicated but it makes the topic even muddier. Because [now] it’s hard to take a position at all.

MY: You can’t say, “Only those who benefit the society can come in here,” because you don’t know who it’s going to be.

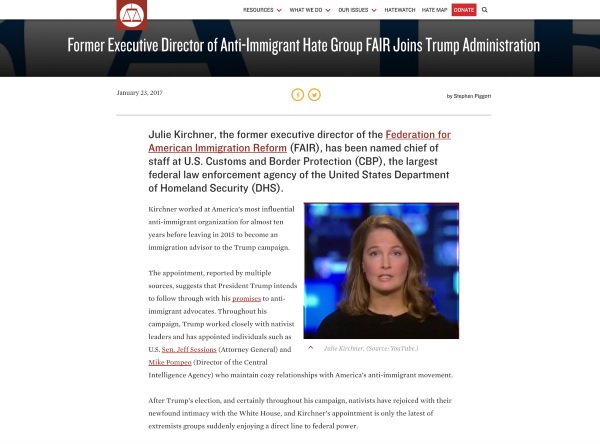

PS: Well, that’s another argument too. There is now a representative from this anti-immigrant group in the Trump White House. So they want people with high IQs.

Well, you start thinking, well, where do you stop? You start down this road, but then if you start down this other trajectory, then you have to start to question the whole enterprise of having these kinds of immigration rules at all. As you say, you don’t know, there could be many illegal immigrants that could be incredibly, incredibly productive and successful in this society.

MY: And, traditionally, all the immigrant groups came in and they did all the hard labor. Traditionally, all of them. From the Irish right up until the Asians.

RYA: Oh, absolutely.

* * *

Continue reading the extended version of this conversation.

Rosanna Yamagiwa Alfaro has written and produced several plays. She is also the writer and narrator of the documentary Japanese American Women: A Sense of Place. Rosanna was also a 2010 Huntington Playwriting Fellow and received a 2011 MCC Artist Fellowship in Playwriting. Several of her plays have been produced nationally and abroad and anthologized. She graduated from Harvard and received an M.A. from Berkeley. She lives with her husband, Gustavo Alfaro in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Margaret Yamamoto is co-president of the New England Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. She has addressed audiences on the topic of Japanese incarceration during WWII. Margie retired recently after more than 40 years in the communications and public relations fields. She worked for Boston PBS television station WGBH for most of her tenure and has served on the boards of the Japan Society of Boston, the Asian Pacific American Agenda Coalition, and the Cambridge Center for Adult Education.

Pia Sawhney (@poltx) produced, edited and directed the interview. She is an award-winning reporter, and has collaborated on productions for PBS FRONTLINE, the Los Angeles Times, Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. Pia holds a Masters degree in international relations from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, a Masters degree in genetics and broadcast journalism from NYU, and an undergraduate degree from Bryn Mawr College. She has published work to the Huffington Post, The Washington Post and other outlets.