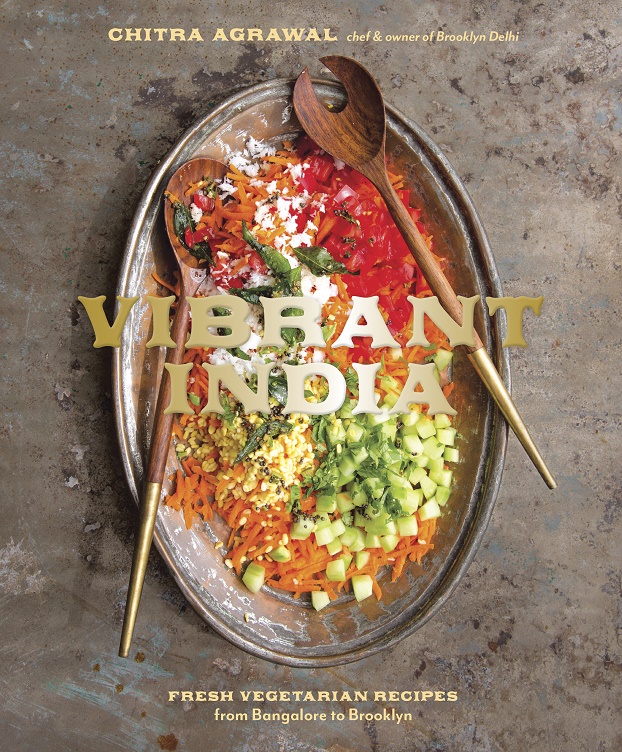

One of the first photographs in Chitra Agrawal’s Vibrant India: Fresh Vegetarian Recipes From Bangalore to Brooklyn (Ten Speed Press) shows her great aunt, grandmother and parents shopping for guava in the bylanes of Delhi. They are all hovering around the vendor and his make-shift produce stand draped in red cloth. Having grown up in India, I can fill in the sounds, the smells, and the banter that color the neighborhood market, and in which the vegetarian recipes of Vibrant India are rooted. That photograph and the two preceding it, also of open-air markets, are a signal — they herald the nature of the food discussed and showcased in the cookbook: recipes made with indigenous ingredients sourced from local farmers who, in most instances, are also the vendors.

This reality shapes one of the most vexing conundrums of the immigrant’s journey — how do you reproduce the foods and flavors of your heritage in a land that has neither the necessary implements nor many of the ingredients? Flavors that relied, for the most part, on hyper-local produce, indigenous spices and implements tailored to make particular types of dishes?

“How do you reproduce the foods and flavors of your heritage in a land that has neither the necessary implements nor many of the ingredients?”

Immigrants become masters of improvisation in the kitchen without even meaning to. No thin, green Indian chilies? No problem! Jalapeños will do just as well. Spinach stands in for fenugreek leaves (with a dash of roasted fenugreek powder added at the end of the cooking process to bring in the aroma of fenugreek missing from the spinach), pitas stand in for rotis, and, in a pinch, paprika must stand in for red chili powder. Where small eggplants are not available, the big ones will just have to do. The substance of the resulting dish is pretty close to the original but the form might be different. But will the stomach recognize the difference or care?

The cookbook’s author has written a journal of vegetarian recipes at The ABCDs of Cooking since 2009. She was born in America and thus might have had some of the ingredient substitutions and tweaking of methods handed down to her from her first-generation immigrant parents (as I do with my children) while simultaneously growing up with a more intimate familiarity with the other cuisines widely available in America. They render her forays into experimentation in technique, method and melding of ingredients refreshingly bold and adventurous.

Over the last decade or so, the market for international produce, grocery items and kitchen devices has improved tremendously as has access to information — and that includes access to recipes hitherto shared only by word of mouth or via air mail within small circles of family or friends. Now there are online repositories of recipes, cooking shows, blogs and Facebook groups sharing recipes with abandon. Not only can immigrants more easily tap into the treasure trove of their own cuisine more easily, but so can anyone who doesn’t have the remotest connection to a particular country or region. There is hardly anything these days that prevents anyone from trying any cuisine from any part of the world. In fact, it’s the opposite — there are ample resources to push even the most recalcitrant cook to broaden their horizons.

“Agrawal’s experimentation in technique, method and melding of ingredients is refreshingly bold and adventurous.”

If food is meant to be the bridge between cultures then this is a brave, new, happy world we now live in, and it is into this state of affairs that Vibrant India dips its toes. The recipes come from the southern region of the state of Karnataka in South India (with a few recipes that are native to other states), and they are all vegetarian recipes. The diversity of cultures in India is breathtaking; her languages and dialects, dress, landscapes, art forms, and most definitely cuisine are more diverse than those found in most other countries. Even within a state, the northern regions might have a vastly different cuisine from its coastal, southern or interior regions.

Divided into nine chapters with additional sections that seek to introduce a section of the readership to a cuisine’s methods and techniques they might be unfamiliar with, the cookbook is dense with information and ideas. The chapters are each devoted to a meal or one component of a meal, and include recipes to be made on occasion.

For anyone who grew up in the same region that many of the book’s recipes originate from, they are instantly recognizable — recipes such as Nimbe Saaru (Lemony Lentil Soup), Khara Huggi or Pongal (Yellow Lentil and Rice “Risotto”), or Vangi Baath (Fragrant Eggplant and Green Pepper Rice). Although their globalized names might take a little getting used to, they should not come as a surprise.

For anyone who grew up in India but now lives anywhere other than India, the spirit that infuses many of the ideas for new dishes described in the book are instantly familiar too. This is where Vibrant India shines and gets exciting — melding old and new ingredients, old and new methods, in old and new devices — to arrive at a result that is a tip of the hat to delicious ingenuity.

The recipe for “Vangi Baath” Roasted Brussels Sprouts and Cauliflower is one example. Vangi Baath powder is a spice blend that is used to cook together rice, eggplant and green bell peppers and that dish is an integral part of the south Karnataka repertoire. Roasting vegetables in the pan with some salt and pepper is a technique most Americans are familiar with, and which I turn to often when I’m looking for vegetables to go with a pasta dish. But this use of the Vangi Baath powder to roast vegetables not usually associated with the original rice dish (with Brussels sprouts, no less!) in the oven is nothing if not inspired.

“The recipes come from the southern region of the state of Karnataka in South India (with a few recipes that are native to other states), and they are all vegetarian recipes.”

For anyone who has no connection to India other than a passing familiarity with their neighborhood Indian joint, Vibrant India is a revelation — a cookbook of Indian recipes with no mention of Butter Chicken or Chicken Vindaloo. Yes, there are thousands of regional recipes in India that are as flavorful and delicious as most recipes commonly served in Indian restaurants. The Meal Planning and Sample Menu chapter is particularly helpful. Not far behind are the chapters on starter grocery lists and how to use the book.

If there is one thing (or two or three) to take away from Vibrant India, it is that the vastness of Indian cuisine is breathtaking, there is a whole treasure trove of recipes waiting to be discovered, and that making Indian food at home is not complicated after all. To this end, I would have preferred the method sections in each of the recipes to be numbered steps rather than paragraphs. It’s easy to lose your place in the method and without a short-hand way to mentally map the recipes it’s difficult to find your way back. The next best thing to do is what I do in the cookbooks I own — make notes with abandon and make your own roadmap.

The following is a recipe from Vibrant India that I needed no roadmap for. It is, as Agrawal says, comfort food, and with good reason. It’s one of the first solid food combinations fed to babies when they transition to ‘real’ food. Yellow lentils, rice and ghee with a dash of salt and crushed black pepper. Always served warm by the hand of the person feeding baby at the moment.

Here is the grown-up version but just as simple and just as delicious. I couldn’t get past it when I came to it in the cookbook when I was deciding what to make and I’m glad I didn’t.

Yellow Lentil and Rice “Risotto” from Chitra Agrawal’s Vibrant India: Fresh Vegetarian Recipes From Bangalore to Brooklyn

Khara Huggi or Pongal

All seasons | Serves 4

Fittingly named, huggi is the ultimate comfort food. You definitely feel like you’re being hugged when eating it. It’s made from rice, yellow lentils called moong dal, which are split mung beans without skin, and black pepper and cumin seeds fried in ghee or butter. The lentils and rice cook together, making a creamy, rich dish resembling risotto. Traditionally, this dish is served with additional melted butter or ghee on top. I usually pair it with tangy accompaniments, like raitas, my green beans palya, cilantro coconut chutney, Brooklyn Delhi tomato achaar, or even a dash of lemon juice. Feel free to substitute red lentils for the yellow variety if that’s what you have on hand.

Similar rice and lentil dishes exist throughout India, and are known by different names. This rice dish is also known as pongal in South India and is often served during the Hindu harvest festival of Sankranthi. There are spicy and sweet versions. You can make the sweet version by omitting the black pepper, cumin, asafetida, and ginger and adding sugar, golden raisins, and ground cardamom.

1 cup basmati rice, preferably Dehraduni, or jasmine rice

1⁄3 cup moong dal or

red lentils

1⁄4 teaspoon turmeric

powder

4 tablespoons plus

1⁄2 teaspoon ghee or unsalted butter

1 teaspoon peeled, grated fresh ginger

2 tablespoons cashews, broken into large pieces

1 teaspoon cumin seeds or ground cumin

1⁄2 teaspoon whole black

peppercorns or freshly ground black pepper

1 1⁄4 teaspoons salt

1⁄4 cup dried unsweetened

shredded coconut

Big pinch of asafetida (hing) powder

Wash the rice in several changes of water until the water runs clear. Soak the rice in water, generously covered, for at least 30 minutes. (This is optional but results in softer, more evenly cooked rice.) Drain thoroughly using a fine-mesh sieve.

In a soup pot, dry-roast and stir the lentils continuously over medium heat until they are golden brown and have a nutty aroma, 2 to 3 minutes. (This step is optional but reduces the stickiness of the dal.) Thoroughly wash the lentils using a fine-mesh colander. Return them to the pot, together with the rice, and add 31⁄2 cups of water. Bring to a boil. Skim the foam off the top. Add the turmeric powder, 2 tablespoons of the ghee, and the ginger to the boiling mixture.

Cover and cook over low heat until the rice and lentils are completely cooked, about 20 minutes. At this point, the grains will look separate. Add another 1⁄2 cup of water and continue to cook over medium-low heat, partially covered, for about 5 minutes. When you stir the mixture, it should have a creamy consistency. Feel free to mash the rice and lentils with a spoon. The consistency should be similar to a risotto. Turn off the heat.

While the rice and lentils are cooking, put 1⁄2 teaspoon of the ghee in a tempering pot or small pan over medium heat. Add the cashews, stirring them until they are fragrant and turn golden brown, a few minutes. Set the cashews aside to cool in a bowl lined with a paper towel. If using cumin seeds and peppercorns, roughly crush them in a mortar with a pestle. Set aside.

When the rice and lentil mixture is cooked, mix in the salt, coconut, and fried cashews, reserving some cashews for garnish.

Put the remaining 2 tablespoons of ghee in the tempering pot or small pan over medium heat. When melted, add the crushed black peppercorns and cumin seeds and the asafetida. Fry for a few seconds until fragrant. Turn off the heat.

Immediately pour the spiced ghee over the rice. To get all of the spiced ghee out of the pot, put a spoonful of the rice mixture into the pot, stir, and spoon it back into the rest of the dish. Taste for salt and adjust as needed. Garnish with the reserved cashews. Serve hot.

When reheating, add a little water to loosen up the dish, as it has a tendency to dry out.

* * *

Sujatha Bagal is a Washington, D.C.- based freelance writer and blogger. Her essays, articles and stories have appeared in various online and print publications, including Pregnancy, Mint Lounge, ForbesLife India and The Smart Set (links available here). She is currently working with her mom-in-law on a cookbook featuring regional Karnataka cuisine. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.