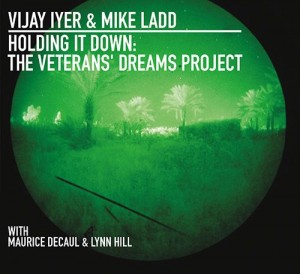

Tuesday marked the release of “Holding It Down: The Veterans’ Dreams Project,” the third collaborative album release by poet/performer Mike Ladd and Grammy-nominated composer/pianist Vijay Iyer over the span of 10 years. During the last few years, Ladd interviewed dozens of veterans of color involved in America’s conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and together with Iyer, channeled their experiences through the medium of dreams. A portion of the album proceeds benefit Student Veterans of America. I spoke with Iyer on the phone the morning of September 10 about the album. Below is an edited excerpt from that interview.

I’m not a jazz expert — but in your experience — how uncommon are projects like “Holding It Down?”

It’s rare that you see something in our culture that deals with the fact that we’ve been at war for over a decade. It’s often something that doesn’t get addressed or acknowledged. That was part of why we choose to do this. I won’t say it’s been ignored, but I think the overall sense is a lot of willful ignorance or obliviousness toward the veterans community. It’s something you just don’t talk about — it’s kind of like white guilt.

Is that why your project chose to focus on veterans of color?

We chose veterans of color for partly that reason. These projects of ours explore what the world is like for people of color — particularly after 9/11. Afghanistan and Iraq were two very racialized wars — dehumanization of the enemy was very racialized. So people of color were caught up in that complex rationalization of the enemy and had to find ways to negotiate that element.

What, in your opinion, is the one thing the government should be doing for veterans?

To be honest, a lot has changed since Obama. He has done a lot for their cause. There’s still a huge backlog at the Department of Veterans Affairs — Jon Stewart has made that famously clear. But a lot of programs have improved. [Although] I don’t want to paint a rosy picture or dismiss what is already being done.

What do you want this record to accomplish in the listener? After someone listens to “Holding It Down” what do you imagine happens next?

Well, I think one thing that becomes undeniable is the humanity of those involved. Most people are removed from the waging of war. Most people believe soldiers are trying to dehumanize the enemy, but I think people are trying to dehumanize soldiers. I think this project re-grounds our perspective on who exactly is involved in this process. It’s about imagining community between veterans and civilians.

Which song touches you the most?

Listening to veteran Lynn’s Hill’s “Capacity” has its own kind of impact. That piece stands for the project as a whole. Also “Shush” by Maurice Decaul, another veteran. It has a kind of intensity — just a kind of frankness with the details.

I noticed the song “My Fire” has a bit of old-school Bollywood, right?

It’s actually a sample from old-school Tamil film music. We are dealing with dreams — and things enter how they enter. That film track had a certain energy — an atmosphere of bliss and nostalgia — in contrast to the poem.

What surprised you about making this album?

A lot. For example, one night we performed live and somebody from the Department of Defense came to see the show. Afterwards, he asked Lynn, “What can we do to fix the predator drone program?” To me that was surreal and preposterous — that a bunch of artists could create something that would prompt the Department of Defense to even ask a question.

Did working on this project confirm your own ideas about military life?

It continued to complicate the picture for me in a healthy way. I didn’t come in with any assumptions that I was conscious about — but I also didn’t really know what to expect. I found that veterans are as diverse as any sector of society — in fact, more so in the sense that there are more people of color in the military than there are proportion-wise in the United States.

That was also impacted by 9/11 — in the face of a racialized war, a brown-skinned enemy and all the heightened paranoia about brown-skinned people at home — there was a wave of enlistment from white people and particularly poorer white people. So that transformed the demographics a little bit. It just created a 21st century dynamic in the military.

As a child, did you ever harbor dreams of enlisting?

It never really occurred to me as a possible thing that I might do. I was like any other American boy — I had war-related toys and guns. I know that Mike did and that’s part of the reason he made this project. He talks about it in the song called “Costume.” Mike has this ongoing fascination with war history and war toys — he makes these room-sized diaromas.

What would you do if your child ever decided to join the military?

I’ve found that being an artist in NYC connected to bourgeois intellectuals and people who call themselves pacifist, that we don’t really know anything about military life. I’ve found that it’s been possible to try and connect with the military community and find out who they are, why they made the choice that they made and not try to judge them. As a parent I can’t imagine what it would be like to see my child make that choice and put herself at risk.

Kishwer Vikaas is a co-founder and editor of The Aerogram. Find her on Twitter at @Phillygrrl or email her at editors@theaerogram.com. Follow The Aerogram on Twitter @theaerogram.