A couple months ago, I went on a Tinder date with someone I knew from college. Knew is maybe too strong of a word — we had both participated in a photo shoot for my school newspaper four years ago. We went to a cafe in Berkeley where he was currently a grad student and chatted about what we had been up to since then. He had recently moved back to the Bay after living in Australia with his girlfriend, with whom he separated when his visa status ran out. He told me that she was dating a girl now. “Maybe she’s always been into that,” he said. I felt compelled to remind him that some people like both.

The reason I was on this date in the first place is that I had just been broken up with and needed a quick boost of self-esteem. I had dated this person for about three months, until we had approached the limit of casualness. He told me he wasn’t ready for a serious relationship. When we met up in Dolores Park to talk, he said he hadn’t thought that I would become emotionally attached to him because he was a man. I felt compelled to remind him that some people like both.

Instead, I thought back to our first date when I told him I liked women, too. He didn’t seem to think much of it. I thought back to the time we went to Point Reyes on a windy Sunday, spread out a blanket on the beach, got high and watched the waves crash onto the shore. We talked about previous relationships and I told him that my ex was trans, and he asked me if my feelings changed when they began to transition. I go both ways, I told him, so my feelings didn’t really change.

In fact, I had always envied this particular ex for their ability to exist in two worlds at once. When I knew them as a woman, they were beguiling in their beauty and ambiguity. They told me once that the men who hit on women at bars would try to pick fights with them. I was always caught off guard, then, in the moments when their femininity made itself known; like when I tickled them and they would laugh, begging me to stop, their voice so tender it broke my heart.

A year later, I used male pronouns in our intimate conversations. They didn’t seem so different, to me at least. I thought of them as a shapeshifter, slippery and undefinable. I wanted to go to this liminal space where they existed that eschewed the rules of gender. At the same time, I was struggling with something undefinable in myself, in my attraction to others and how that informed who I was. I had never really questioned my sexual identity until the year after I fell in love with someone whose own identity was intangible in ways I couldn’t understand.

“I had never really questioned my sexual identity until the year after I fell in love with someone whose own identity was intangible in ways I couldn’t understand.”

But sexuality is only one facet of what makes a person. In other ways, I have questioned my identity for so long that the questioning has become an integral part of it. I was born in the United States to immigrant parents, so existing in liminal space is quite familiar to me. It took my parents 20 years, but they have transitioned into English-speaking, always-voting, small-business-owning citizens, rightful proprietors of the American Dream. My parents’ story is one of success, but it belies the sacrifices that were made along the way. I’m like a plant without roots, re-potted in foreign land.

In a way, this is freedom. I can replant myself anywhere in the world. While I am privileged as an American citizen, my identity belongs to neither my parents nor my country; no one else can define it for me. Still, I’ve spent most of my life trying to pass as something less complex, more straightforward. This led to skipping lunch at school when I knew the smell of spices from my leftovers would elicit questions, mispronouncing my name for the ease of others, straightening the curls out of my hair and dating white men in hopes that their proximity would negate my otherness. I remember digging in my heels before weekend temple visits, refusing to wear a sari or shalwar at special events, insisting upon my Americanness whenever possible. The ordinary trials of high school became extraordinarily difficult as I tried to keep track of my double life.

It wasn’t until college that I learned that my in-between status was something of value, even coveted by others. It wasn’t until my culture became fashionable through bindis, yoga and secular spirituality that I realized I did not have to be grateful for crumbs of acceptance. It wasn’t until I took my white boyfriend to an Indian restaurant on our first date that I understood I did not have to be ashamed of where my family came from.

“I was born in the United States to immigrant parents, so existing in liminal space is quite familiar to me.”

In India there is a widely recognized third gender that is neither man nor woman. Known as hijras, this community is considered sacred. When I spent a summer in Mumbai I would see them regularly on the train, dolled up in jewelry and beautiful saris, walking up and down the cars asking for money. If you refuse to give money to a hijra, she could choose to curse you, so it is considered bad luck to turn down their requests. Queerness has long been a part of Hindu mythology, and while remnants of British imperialism name homosexuality as a crime under law, we still understand that something as complex as gender or sexuality is not so easily contained.

I thought about this during a date I went on with a woman I met at a bar last month. She wore her hair cropped close on the sides and long on top, like many of the men in Oakland do. She wore a button-down shirt and pants despite the evening heat that had me sweating in shorts and a tank top; in these respects, femmes have it easier than others. She told me that she has only ever dated women.

I found myself hesitating to tell her that the last person I dated was a man. My best friend from back home, who is a lesbian, confirmed my hesitation. “I am always nervous dating bisexual women,” she said, “because I’m afraid that they will leave me for a man.” Once again, I find myself leading a double life.

There’s a saying in the queer community that the acronym LGBT is ordered from most to least accepted. L and G are easy enough to understand, but B and T require a bit more nuance. What does it mean to identify as both, or neither? When categories are not enough? What does it mean to exist between worlds?

“I am starting to understand ambiguous identity less as a handicap, and more like a superpower.”

For now, I am still answering this question, but it has become easier to leap from one world to another. I am starting to understand ambiguous identity less as a handicap, and more like a superpower. It’s a movement towards reconciliation of paradoxes; that I can be at once a citizen of the most powerful country in the world, and also feared by its citizens who don’t think I belong here; that I can be both straight and gay, and confusing to both. I have to hold both ends of these continuums in my mind at once and find a way to somehow make them work together.

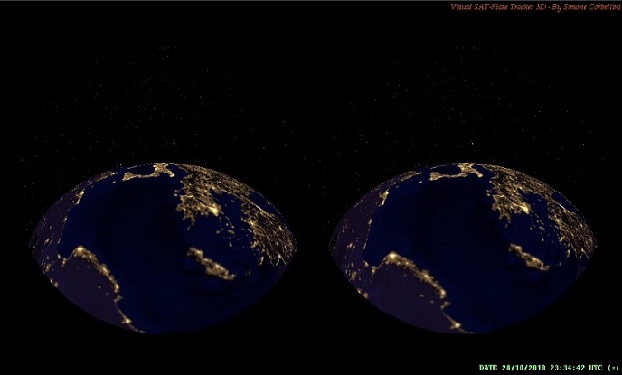

It’s a juggling act analogous to a stereograph, where you look at two side-by-side images with unfocused eyes until a three-dimensional image pops out. My identity has many dimensions and I have a lifetime to map them. I can learn to adapt and be open, to be nimble to navigate them as they continue to shift in and out of focus. I can learn empathy for those who exist in those dimensions and their intersections, in those worlds and the spaces between them. I can learn to hold and listen to their stories so they don’t slip through the cracks.

* * *

Mohana Kute is a nonprofit communications professional in Oakland, CA. She writes about gender, sexuality, diaspora and identity. This post originally appeared on her personal blog.